| Journal of Hematology, ISSN 1927-1212 print, 1927-1220 online, Open Access |

| Article copyright, the authors; Journal compilation copyright, J Hematol and Elmer Press Inc |

| Journal website https://jh.elmerpub.com |

Case Report

Volume 14, Number 6, December 2025, pages 324-328

A Complex Case of Hemophagocytic Lymphohistiocytosis Secondary to Untreated Hepatitis C: Diagnostic Challenges

Zachrieh Alhaja, c, Alexander Konopnickib, Zaid Almubaida, Khushali Royb, Thomas Leb, Paul S. Parkb

aJohn Sealy School of Medicine, University of Texas Medical Branch, Galveston, TX 77555, USA

bDepartment of Internal Medicine, University of Texas Medical Branch, Galveston, TX 77555, USA

cCorresponding Author: Zachrieh Alhaj, John Sealy School of Medicine, University of Texas Medical Branch, Galveston, TX 77555, USA

Manuscript submitted June 12, 2025, accepted August 14, 2025, published online December 30, 2025

Short title: HLH Triggered by Untreated Hepatitis C

doi: https://doi.org/10.14740/jh2101

| Abstract | ▴Top |

Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH) is a life-threatening hyperinflammatory syndrome caused by uncontrolled activation of cytotoxic T cells and macrophages, leading to cytokine storm and organ failure. Secondary HLH is the acquired form that is commonly triggered by underlying malignancies, autoimmune diseases, or infections. While Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) is a common infectious trigger for HLH, hepatitis C virus (HCV) is rarely reported in the literature. Herein, we present the case of a patient with HLH with multiple possible infectious triggers that was ultimately attributed to HCV. A 61-year-old male with a history of untreated HCV was admitted with concerns for septic shock. Infectious workup was largely negative throughout his hospitalization. Lumbar puncture was concerning for a fungal meningitis, but fungal workup was negative except for a positive Blastomyces dermatitidis antibody. In addition, acid-fast bacilli culture eventually grew Mycobacterium porcinum (M. porcinum). He was treated with broad-spectrum antibiotics and anti-fungals but continued to fever. He met five of eight criteria per HLH-2004 protocol and was initiated on HLH-directed therapy with immediate resolution of his fevers. A Karius test did not identify pathogenic levels of Blastomyces dermatitidis or M. porcinum in the serum, and the causative trigger was determined to be his untreated HCV. This case highlights the importance of early recognition and treatment of HLH in a patient with fever of unknown origin. It brings attention to HCV as a highly unusual trigger of HLH. It also illustrates the difficulty in addressing the underlying source of secondary HLH when a broad infectious workup yields several rare but possible pathogens.

Keywords: HLH-2004; HLH; HCV; Cytokine; Immune-mediated inflammatory disease

| Introduction | ▴Top |

Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH) is a rare, potentially life-threatening hyperinflammatory condition caused by the overactivation of cytotoxic T cells, macrophages, and natural killer (NK) cells, which can lead to a cytokine storm and ultimately organ damage [1].

HLH can be classified into primary or secondary HLH. Primary, or familial, HLH involves genetic mutations such as PRF1, UNC13D, STXBP2, which affect the cytotoxic activation of T lymphocytes, leading to unregulated activation. Secondary, or acquired, HLH occurs with an underlying trigger such as infection, autoimmune diseases, and malignancies [2, 3]. Among secondary causes, the most common are due to malignancies, accounting for 42% of secondary HLH cases [4, 5]. The next most common cause is autoimmune conditions, which account for 40.9% of cases according to a Chinese cohort, and is often associated with systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis and adult-onset Still’s disease [6]. Infections can also be a common trigger, with Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) seen in 69% of secondary HLH due to infections, and less commonly cytomegalovirus (CMV) [5].

HLH clinically presents as persistently high fevers, cytopenias, hepatosplenomegaly, and may sometimes include neurologic and hepatologic dysfunction. The Histiocyte Society developed the HLH-2004 criteria to serve as a diagnostic and therapeutic guideline for HLH syndrome, which encompasses both HLH disease and conditions that mimic HLH, such as severe infections or autoimmune diseases. One of the major challenges in clinical practice is distinguishing true HLH disease from these mimics, as both can fulfill the diagnostic criteria. The diagnosis of HLH is established if one of two criteria are fulfilled. The first criterion is a molecular diagnosis consistent with HLH. The second criterion is if five of eight objective criteria are met. These eight criteria are as follows: fever, splenomegaly, cytopenias (affecting ≥ 2 lineages in the peripheral blood), hypertriglyceridemia and/or hypofibrinogenemia, hemophagocytosis in bone marrow, spleen, or lymph nodes, low or absent NK-cell activity, ferritin ≥ 500 µg/L, and soluble interleukin (IL)-2 receptor ≥ 2,400 U/L. HLH-2004 chemo-immunotherapy includes etoposide, dexamethasone, and cyclosporine which aim to manage the excessive immune activation and inflammation. However, treatment of HLH disease is often more nuanced and may involve additional modalities such as antithymocyte globulin (ATG), biologic agents like emapalumab, or hematopoietic stem cell transplantation [7]. In secondary HLH, treating the underlying condition can be crucial for controlling HLH [8].

Our case report presents an interesting situation where our patient was diagnosed with HLH and initiated on treatment per the HLH-2004 criteria. However, after an expansive and thorough workup, pinpointing the underlying secondary trigger of HLH was elusive. This case adds to the limited findings of hepatitis C virus (HCV)-induced HLH in the literature. Early recognition of this association in patients may provide favorable outcomes.

| Case Report | ▴Top |

Investigations

A 61-year-old male with a past medical history of untreated HCV and hypertension presented to the emergency department for a 3-week history of generalized weakness. Associated symptoms included fatigue, fevers, chills, night sweats, and an unintentional 40-pound weight loss. He denied any rash or skin lesions, and none were noted on physical examination. Vital signs on admission showed a blood pressure of 92/53 mm Hg, heart rate of 122 beats per minute (bpm), respiratory rate of 22 breaths per minute, and temperature of 38.1 °C. His complete blood count showed a white blood cell count of 0.49/µL, hemoglobin of 6.2 g/dL, and platelet count of 6 × 103/µL. Comprehensive metabolic panel showed a creatinine of 2.32 mg/dL, alanine aminotransferase of 314 U/L, and aspartate aminotransferase of 491 U/L. Ferritin was elevated to 7,210 ng/mL. Lactic acid was elevated to 6.93 mmol/L. Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), influenza A and B, and respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) were negative. Blood cultures were drawn, and patient was started on broad-spectrum antibiotics and fluid resuscitation for presumed septic shock.

Diagnosis

Despite broad-spectrum antibiotics and fluid resuscitation, the patient remained febrile and pancytopenic. The patients’ blood cultures also remained negative. Hematology Oncology was consulted with concerns for HLH. On day 6, his IL-2 receptor level returned with a value > 4,340 U/mL. A bone marrow biopsy was obtained which showed pancytopenia with hemophagocytosis and polyclonal plasma cells. Per the HLH-2004 criteria, the patient met more than five criteria for HLH and was started on IV dexamethasone and etoposide with resolution of his high-spiking fevers and improvement in his hemodynamics, as well as kidney and liver function.

Genetic testing was not available during this admission. While primary HLH was considered less likely given the patient’s age and history, we cannot fully exclude an underlying genetic predisposition.

Treatment

Infectious Disease was consulted for the fever of unknown origin and identification and treatment of the underlying infectious trigger of HLH. A lumbar puncture showed cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) with low glucose (37 mg/dL) and elevated total protein (76 mg/dL), concerning for a fungal meningitis. CSF cultures were pan-negative for bacteria, fungi, and acid-fast bacilli (AFB), and fungal CSF cultures specifically did not yield any growth. Fungal serum serologies were notable for a positive Blastomyces dermatitidis antibody, presumed to reflect prior exposure, as there was no clinical or imaging evidence suggestive of active infection. AFB sputum cultures eventually grew Mycobacterium porcinum (M. porcinum), a non-tuberculous mycobacterium (NTM). However, this was not considered the primary infectious trigger due to lack of systemic features of disseminated NTM infection. Additionally, AFB blood and CSF cultures were negative, and chest imaging did not demonstrate lymphadenopathy or cavitary lesions to suggest NTM dissemination. Given this, empiric antifungal and broad-spectrum antibacterial treatments targeting both pathogens were initiated but later discontinued once the Karius test results and clinical data did not support active infection. Further testing revealed markedly elevated HCV RNA levels (15,460,350 IU/mL) via quantitative nucleic acid amplification testing. The patient had a known history of HCV, having first tested positive 3 years earlier following a period of incarceration. Given the absence of other plausible infectious etiologies, untreated chronic HCV was determined to be the likely driver of HLH in this case. The patient was initiated on direct-acting antiviral therapy with sofosbuvir and velpatasvir during hospitalization.

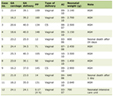

The infectious diagnostic findings across serum, CSF, bone marrow, and sputum are summarized in Table 1.

Click to view | Table 1. Summary of Infectious Workup by Sample Source |

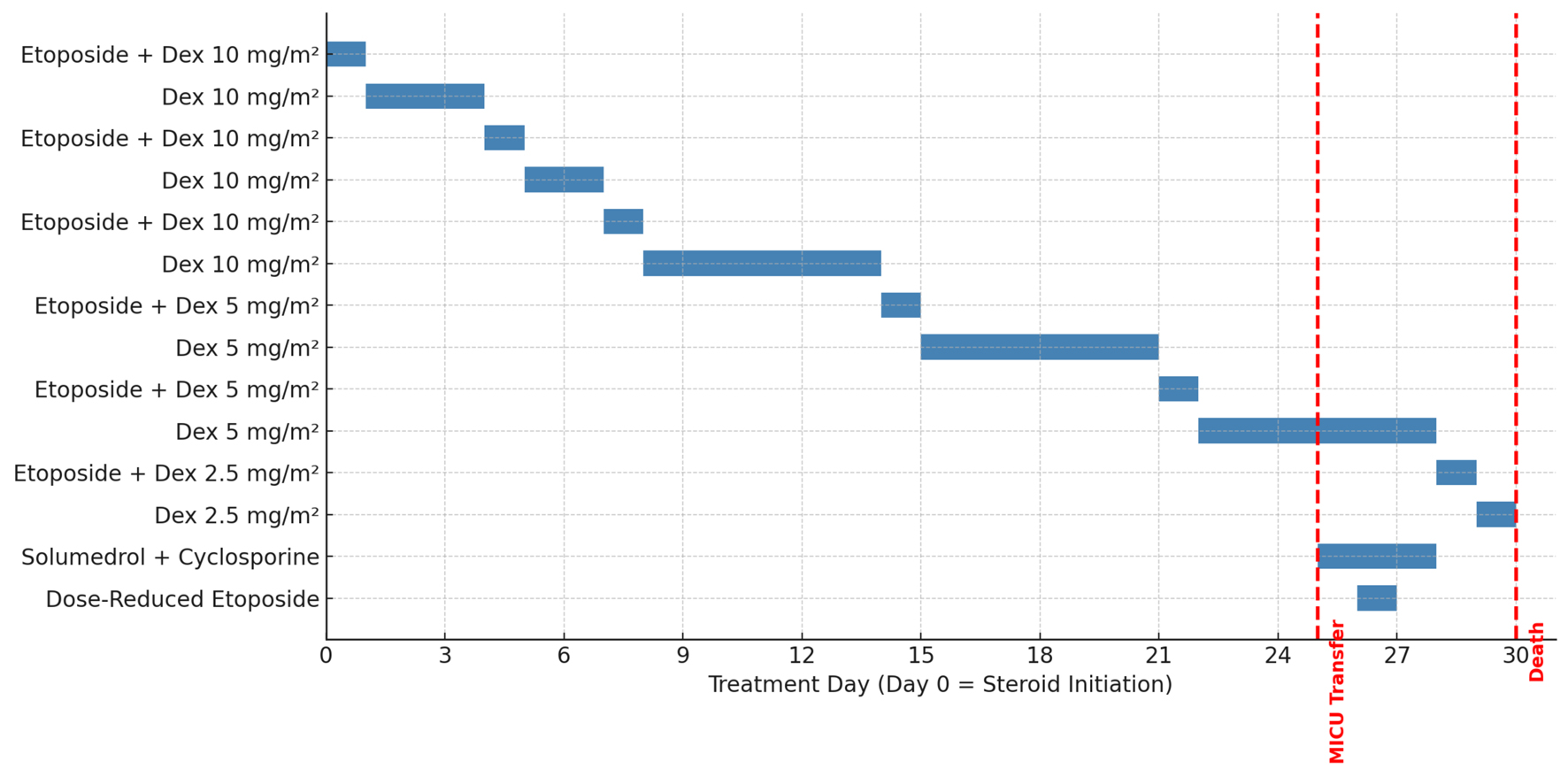

A summary of the anti-HLH treatment course is shown in Figure 1. Day 0 was defined as the initiation of steroid therapy. The patient was managed per the HLH-2004 protocol with etoposide and dexamethasone. Etoposide was administered on days 1, 5, 8, 15, 22, and 29, and dexamethasone was tapered accordingly. On day 26 of treatment, he experienced sudden clinical decompensation requiring transfer to the MICU. Solumedrol 1 g daily for 3 days was initiated, along with cyclosporine 100 mg twice daily. A dose-reduced etoposide was administered on day 27. The patient passed away on day 30 of treatment, prior to completion of the planned steroid taper.

Click for large image | Figure 1. HLH treatment timeline. |

Follow-up and outcomes

Unfortunately, his condition was complicated with new onset supraventricular tachycardia with sustained heart rates of 150 bpm. The patient was transferred to the intensive care unit (ICU), and his transthoracic echocardiogram showed a newly mildly reduced ejection fraction of 45-50% and regional wall motion abnormalities, concerning for HLH cardiomyopathy. The patient continued to deteriorate clinically. Due to his worsening condition, the patient’s family opted to pursue comfort care, and the patient ultimately passed.

| Discussion | ▴Top |

HLH is a rare hyperinflammatory condition caused by excessive activation of cytotoxic cells leading to organ dysfunction [1]. It is commonly triggered by malignancies, autoimmune conditions, or infections. Identification of several potentially pathogenic organisms, like in our patient who had Blastomyces dermatitidis, untreated HCV, and M. porcinum, can complicate the diagnostic picture and delay definitive treatment of HLH.

The patient’s combination of positive results prompted consideration of multiple infectious triggers and required a broad therapeutic approach. A Karius test, which uses microbial cell-free DNA sequencing to detect pathogens, did not identify Blastomyces dermatitidis or M. porcinum. Based on this, Infectious Disease recommended discontinuing broad antimicrobials, reinforcing that untreated HCV was the likely HLH trigger [9].

The association of HCV as a trigger for HLH may be a retroactive diagnosis, confirmed only after clinical improvement following antiviral therapy. Although there are very limited documented cases of HCV-induced HLH, some studies recognize that chronic viral infections such as hepatitis can lead to immune dysregulation and trigger HLH through mechanisms including antigenic stimulation, immune complex formation, and macrophage activation [3, 10, 11, 12]. HCV can also promote chronic inflammation and has been associated with lymphoproliferative disorders like HLH. While viruses such as CMV and EBV more commonly cause HLH, HCV-induced cases may present with a similar clinical picture [5, 10, 12-14].

It is imperative to get a viral PCR in these patients to assess viral load, like the approach of more common viral triggers of HLH, including EBV and CMV [15]. Antiviral therapy is the mainstay of HCV treatment, reducing the viral inflammatory process. Immunosuppression, such as etoposide and dexamethasone, can be used to further reduce inflammation [15]. For refractory cases, hematopoietic stem cell replacement can be considered [9].

This case highlights the importance of early consideration of HLH patients presenting with systemic symptoms and persistent fevers and pancytopenia. Even when a patient’s presentation may be vague or explained by other primary diagnoses, it is crucial to consider HLH. This patient’s overlapping infectious findings made determining the initial trigger difficult, but prompt improvement in our patient after initiating HLH-guided protocol concurrent with HCV treatment supported our diagnosis of HLH secondary to untreated HCV. This case adds to the very limited documented literature of HCV-induced HLH and shows the complexity of HLH presentation and diagnosis.

Learning points

This case highlights the importance of considering HLH in patients with persistent fevers and cytopenias, even when the underlying trigger is unclear. It shows that overlapping infectious findings can complicate diagnosis, making early therapeutic intervention critical. Most importantly, it draws attention to HCV as a potential but underrecognized trigger for HLH, even in immunocompetent patients. Prompt identification and treatment of HLH alongside targeted management of the underlying cause can significantly impact clinical outcomes.

Acknowledgments

None to declare.

Financial Disclosure

None to declare.

Conflict of Interest

None to declare.

Informed Consent

Informed consent has been obtained.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed equally to all aspects of the systematic review. This includes the development of the research question and review methodology, the design and execution of the search strategy, the screening and selection of studies, data extraction, quality assessment, data interpretation, and the drafting and revision of the manuscript. All authors reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript and agree to be accountable for all parts of the work.

Data Availability

The data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

| References | ▴Top |

- Griffin G, Shenoi S, Hughes GC. Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis: An update on pathogenesis, diagnosis, and therapy. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2020;34(4):101515.

doi pubmed - Canna SW, Marsh RA. Pediatric hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Blood. 2020;135(16):1332-1343.

doi pubmed - Al-Samkari H, Berliner N. Hemophagocytic Lymphohistiocytosis. Annu Rev Pathol. 2018;13:27-49.

doi pubmed - Daver N, McClain K, Allen CE, Parikh SA, Otrock Z, Rojas-Hernandez C, Blechacz B, et al. A consensus review on malignancy-associated hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis in adults. Cancer. 2017;123(17):3229-3240.

doi pubmed - Miao Y, Zhang J, Chen Q, Xing L, Qiu T, Zhu H, Wang L, et al. Spectrum and trigger identification of hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis in adults: A single-center analysis of 555 cases. Front Immunol. 2022;13:970183.

doi pubmed - Pei Y, Zhu J, Yao R, Cao L, Wang Z, Liang R, Jia Y, et al. Prognostic factors in patients with secondary hemophagocytic lymphohistioc ytosis in a Chinese cohort. Ann Hematol. 2024;103(3):695-703.

doi pubmed - Summerlin J, Wells DA, Anderson MK, Halford Z. A review of current and emerging therapeutic options for hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Ann Pharmacother. 2023;57(7):867-879.

doi pubmed - Henter JI, Horne A, Arico M, Egeler RM, Filipovich AH, Imashuku S, Ladisch S, et al. HLH-2004: Diagnostic and therapeutic guidelines for hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2007;48(2):124-131.

doi pubmed - Park SY, Chang EJ, Ledeboer N, Messacar K, Lindner MS, Venkatasubrahmanyam S, Wilber JC, et al. Plasma microbial cell-free DNA sequencing from over 15,000 patients identified a broad spectrum of pathogens. J Clin Microbiol. 2023;61(8):e0185522.

doi pubmed - Pease D, Mathew J. Hepatitis C virus associated hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis: case report and literature review. J Hematol. 2013;2(2):76-78.

doi - Diamond T, Bennett AD, Behrens EM. The liver in hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis: not an innocent bystander. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2023;77(2):153-159.

doi pubmed - Brisse E, Wouters CH, Andrei G, Matthys P. How viruses contribute to the pathogenesis of hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Front Immunol. 2017;8:1102.

doi pubmed - Goudarzipour K, Kajiyazdi M, Mahdaviyani A. Epstein-barr virus-induced hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Int J Hematol Oncol Stem Cell Res. 2013;7(1):42-45.

pubmed - Brisse E, Imbrechts M, Mitera T, Vandenhaute J, Wouters CH, Snoeck R, Andrei G, et al. Lytic viral replication and immunopathology in a cytomegalovirus-induced mouse model of secondary hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Virol J. 2017;14(1):240.

doi pubmed - Masood M, Siddique A, Kozarek RA. Adult hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis mimicking acute viral hepatitis. Dig Dis Sci. 2023;68(8):3205-3207.

doi pubmed

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial 4.0 International License, which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Journal of Hematology is published by Elmer Press Inc.