| Journal of Hematology, ISSN 1927-1212 print, 1927-1220 online, Open Access |

| Article copyright, the authors; Journal compilation copyright, J Hematol and Elmer Press Inc |

| Journal website https://jh.elmerpub.com |

Case Report

Volume 000, Number 000, March 2025, pages 000-000

Phosphatidylinositol 3-Kinase Inhibition and Allogeneic Stem Cell Transplantation Can Overcome Chemotherapy Resistance in Refractory Burkitt Lymphoma

Baldeep Wirka, d, Rajeswari Jayakumarb, Jin Limc

aCellular Immunotherapies and Transplant Program, Massey Comprehensive Cancer Center, Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond, VA 23219, USA

bDepartment of Pathology, Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond, VA 23219, USA

cDepartment of Radiology, Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond, VA 23219, USA

dCorresponding Author: Baldeep Wirk, Cellular Immunotherapies and Transplant Program, Massey Comprehensive Cancer Center, Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond, VA 23219, USA

Manuscript submitted February 12, 2025, accepted March 12, 2025, published online March 18, 2025

Short title: Copanlisib Treats Refractory Burkitt Lymphoma

doi: https://doi.org/10.14740/jh2043

| Abstract | ▴Top |

Induction multiagent chemotherapy can cure 70% of adult Burkitt lymphoma patients. However, for the remaining patients, the majority will relapse either during induction chemotherapy or within 6 months after initial complete remission, as in our patient. In this life-threatening presentation where no standard therapy exists with a response rate to salvage chemotherapy of 0% and a median survival of 6 weeks, there is an urgent need for novel, effective approaches to overcome chemoresistance in Burkitt lymphoma. Our report demonstrates that targeting B-cell receptor signaling via the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/protein kinase B (PI3K/AKT) pathway with copanlisib can overcome chemotherapy resistance and achieve complete remission in relapsed Burkitt lymphoma. This novel approach, followed by consolidation with allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation can provide durable complete remission by harnessing the immune graft-versus-lymphoma effect in chemoresistant Burkitt lymphoma.

Keywords: Refractory Burkitt lymphoma; Copanlisib; PI3K inhibitors; Allogeneic stem cell transplantation

| Introduction | ▴Top |

Sporadic Burkitt lymphoma (BL) occurs worldwide and comprises 1% of adult non-Hodgkin lymphoma in the United States and 30% of pediatric lymphoma [1]. The incidence is higher in men, with a male-to-female ratio of 2:1. Extranodal involvement of the leptomeninges and bone marrow is frequent. Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) prevalence is much lower in sporadic BL than endemic BL in sub-Saharan Africa [2]. The focus of this article is sporadic BL in adults.

Real-world data of adult BL patients reported 19% central nervous system (CNS) involvement and 14% primary refractory disease [3]. Treatment-related mortality was 10%, the 3-year progression-free survival (PFS) was 64%, and the 3-year overall survival (OS) was 72% [3]. Intensive multiagent chemotherapy with non-cross-resistant drugs and intrathecal chemotherapy can cure 70% of adults. Of the patients who relapse, the majority have primary refractory disease during initial therapy or experience early relapse within 6 months of achieving the first complete remission (CR), with a median OS of 6 weeks [4]. Only 10% of adult BL patients relapse after 6 months of first CR, for whom the median OS is 5 months [4]. There is no standard therapy for these high-risk chemotherapy-resistant patients. Novel approaches are needed to overcome chemotherapy resistance.

Approximately 8% of BL cases have t(8;14) (q24;q32), resulting in MYC fusion to the immunoglobulin heavy chain, and 20% have MYC fusion to either the lambda light chain t(8;22)(q24;q11) or kappa light chain t(2;8)(p12;q24). All of these lead to constitutive activation and overexpression of the MYC protooncogene, a key promoter of cellular growth and proliferation. TP53 mutation is present in 35% of cases, inhibiting apoptosis further [5]. Recurrent mutations of TCF3 (transcription factor 3) and its negative regulator ID3 (inhibitor of DNA binding 3) occur in 70% of sporadic BL [6, 7]. Mutated TCF3 causes constitutive activation of B-cell receptor/phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase pathway (BCR/PI3K) promoting proliferation and survival of cells. There are no direct MYC inhibitors. Inhibition of the MYC-dependent upregulated proteins such as TCF3, ID3, or PI3K, may provide an alternative approach to blocking this pathway.

Overexpression of MYC leads to activation of PI3K, the upstream activator of AKT, a serine/threonine kinase that regulates cell survival by inhibiting apoptosis [8, 9]. A preclinical model of rituximab-chemotherapy-resistant BL cell lines showed increased phosphorylation of AKT at the serine 473 and threonine 308 residues, indicating AKT activation [8]. Constitutive activation of the PI3K/AKT pathway promotes resistance in BL cell lines, and inhibition of PI3K can sensitize BL cells to chemotherapy [8, 9]. BL cell lines resistant to rituximab-chemotherapy showed increased activation of PI3K/AKT, and inhibition of PI3K resulted in decreased phosphorylation of AKT and in vitro anti-lymphoma activity [9]. The pan-class I PI3K alpha and delta isoform inhibitor copanlisib can sensitize BL to chemotherapy, as shown in this report. Copanlisib has the added advantage of crossing the blood-brain barrier [10].

| Case Report | ▴Top |

A 37-year-old human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-negative male developed a rapidly growing left cervical mass, neck pain, and weight loss. Positron emission tomography-computed tomography (PET-CT) showed bulky 8.1 cm left cervical lymphadenopathy with a maximum standardized uptake value (SUVmax) 26.9 and involvement of the nasopharynx SUVmax 28.3, liver SUVmax 10.3, and left kidney SUVmax 20.6. Cervical lymph node biopsy revealed BL t(8:14) (q24;q32), Ki-67 95%, EBV-encoded RNA negative, and TP53 negative. The cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) cytology was negative for lymphoma. Although the posterior superior iliac crest bone marrow biopsy did not show lymphoma, there were innumerable hypermetabolic lesions within the axial and appendicular skeleton, representing bony involvement. He was diagnosed with stage IV BL.

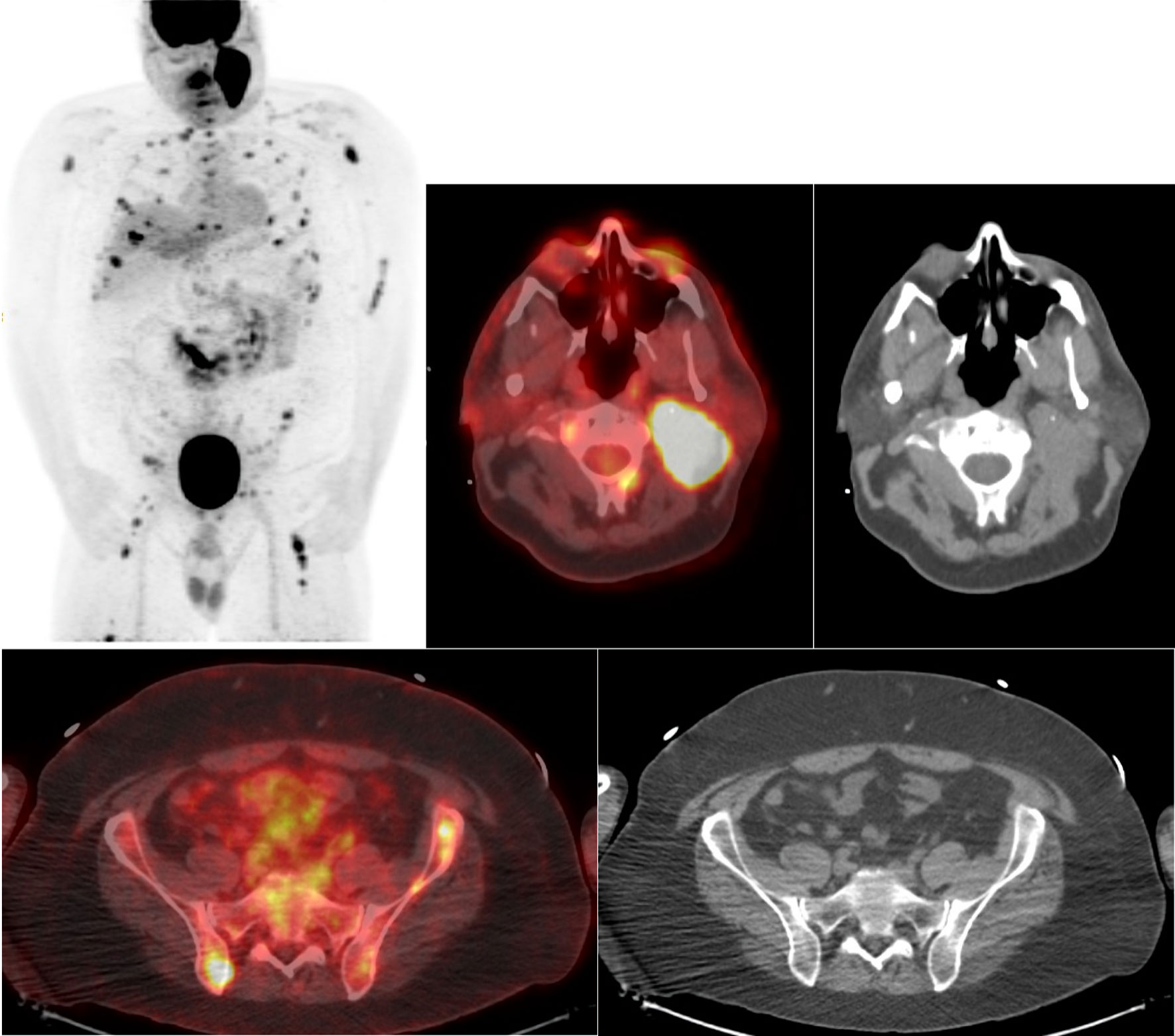

He received six cycles of dose-adjusted etoposide, prednisone, vincristine, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, and rituximab (DA-EPOCH-R) every 21 days with a total of seven intrathecal methotrexate doses attaining a complete metabolic response on PET-CT. One month later, he relapsed with stage IV BL, presenting with bulky cervical lymphadenopathy measuring up to 10.5 cm in greatest dimension SUVmax 19.1 and bone involvement SUVmax 15.5 on PET-CT (Fig. 1). He suffered a sudden asystolic cardiac arrest due to infiltration of the carotid baroreceptors by the bulky cervical lymphoma. After successful cardiopulmonary resuscitation, he had a pacemaker placed.

Click for large image | Figure 1. Initial positron emission tomography-computed tomography (PET-CT) scan. Maximum intensity projection (MIP) with fused PET-CT images and corresponding CT images at the C2 and S1 vertebral levels. |

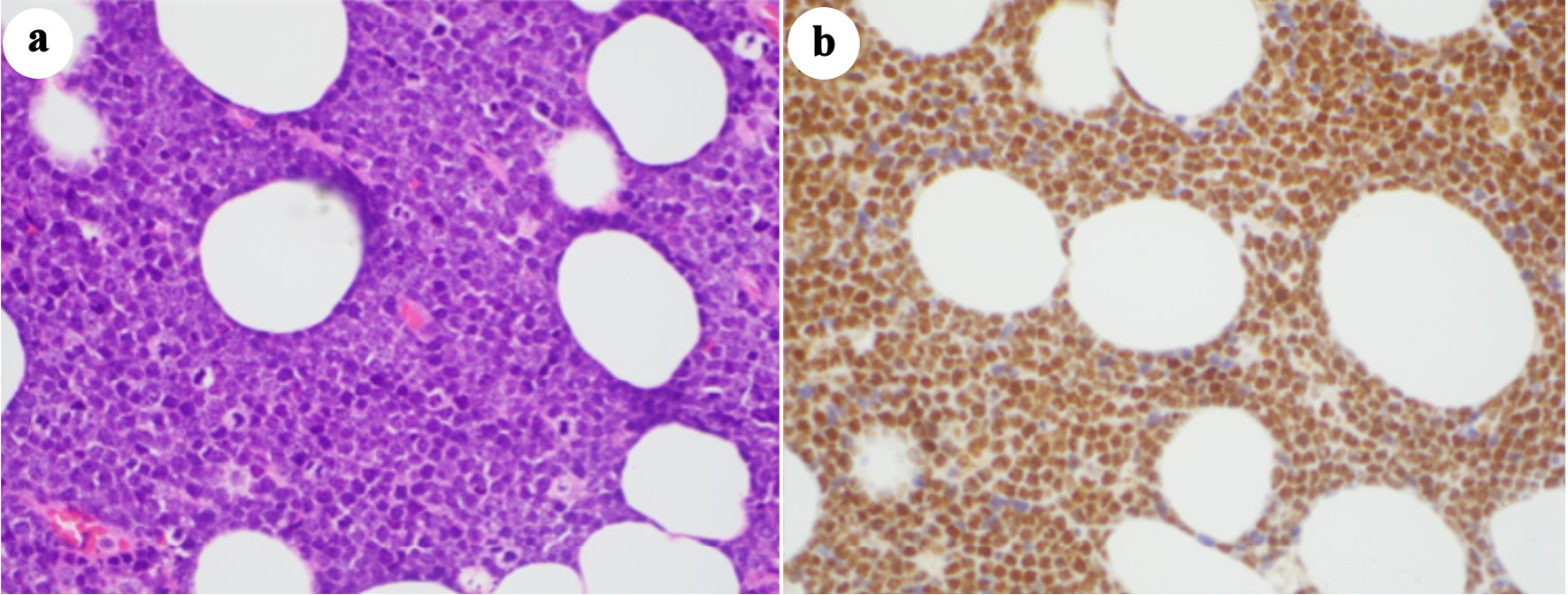

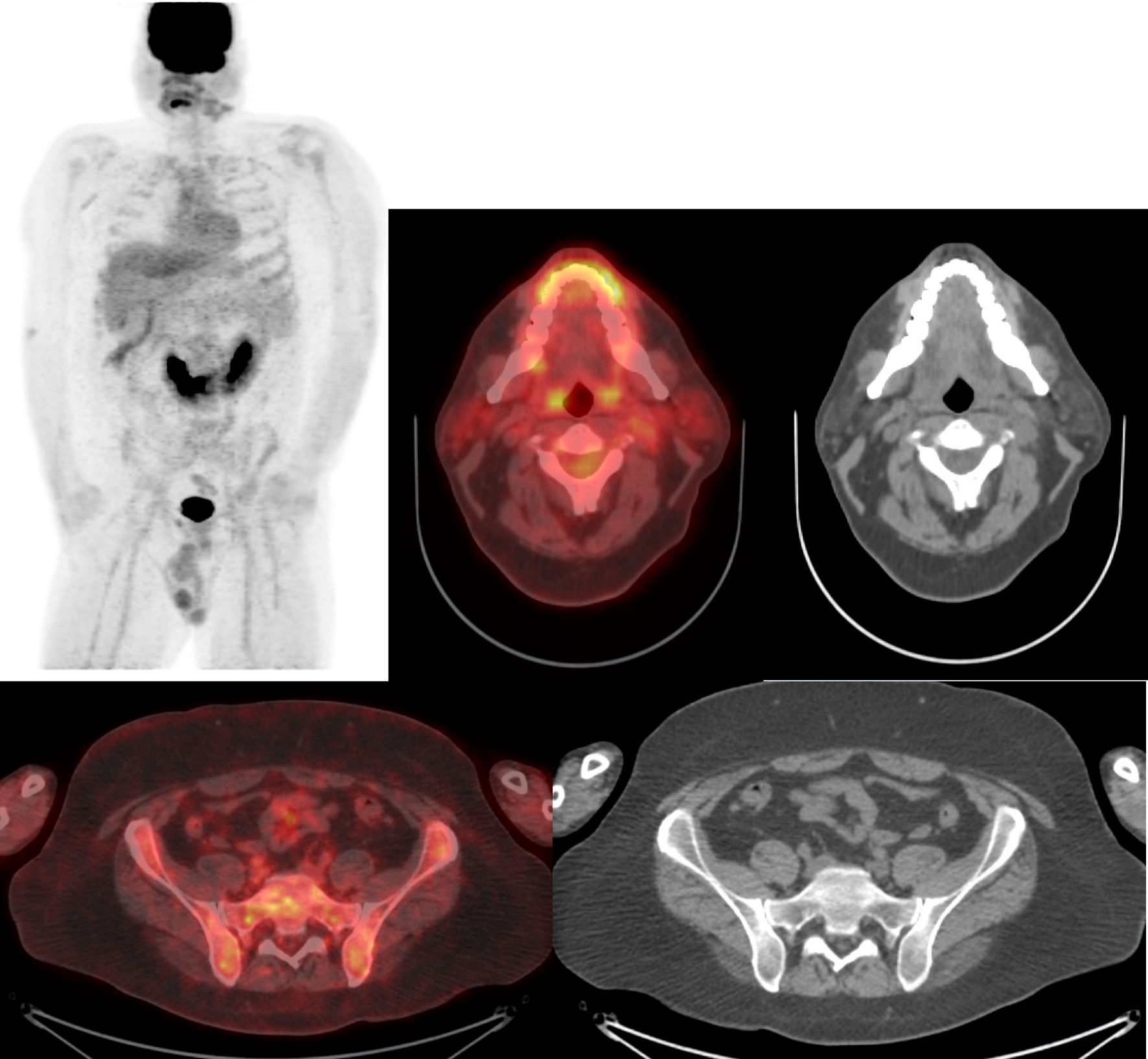

Cervical lymph node biopsy confirmed BL (Fig. 2a). Immunostaining for AKT (Fig. 2b) showed more than 80% of the neoplastic cells stained in a nuclear pattern, indicating increased phosphorylation of AKT at the serine 473 residue. CSF cytology showed BL. He then had three cycles of intravenous copanlisib, a PI3K inhibitor, with DA-EPOCH-R. He also received twice weekly intrathecal methotrexate for six doses until clearance of the malignant cells in the CSF, followed by four weekly doses of intrathecal methotrexate. He tolerated the chemotherapy well and achieved a complete metabolic response on PET-CT (Fig. 3). Bone marrow biopsy and CSF cytology showed no lymphoma.

Click for large image | Figure 2. (a) Hematoxylin and eosin-stained sections (× 400) of the left neck biopsy shows Burkitt lymphoma with diffuse proliferation of monotonous atypical lymphoid cells with scattered tingible body macrophages (starry sky pattern), frequent apoptotic bodies, and mitotic figures. (b) Immunohistochemistry (× 400) for phosphorylated AKT is positive on the neoplastic cells in a nuclear staining pattern. |

Click for large image | Figure 3. Positron emission tomography-computed tomography (PET-CT) scan following chemotherapy and copanlisib. Maximum intensity projection (MIP) with fused PET-CT images and corresponding CT images at the C2 and S1 vertebral levels. |

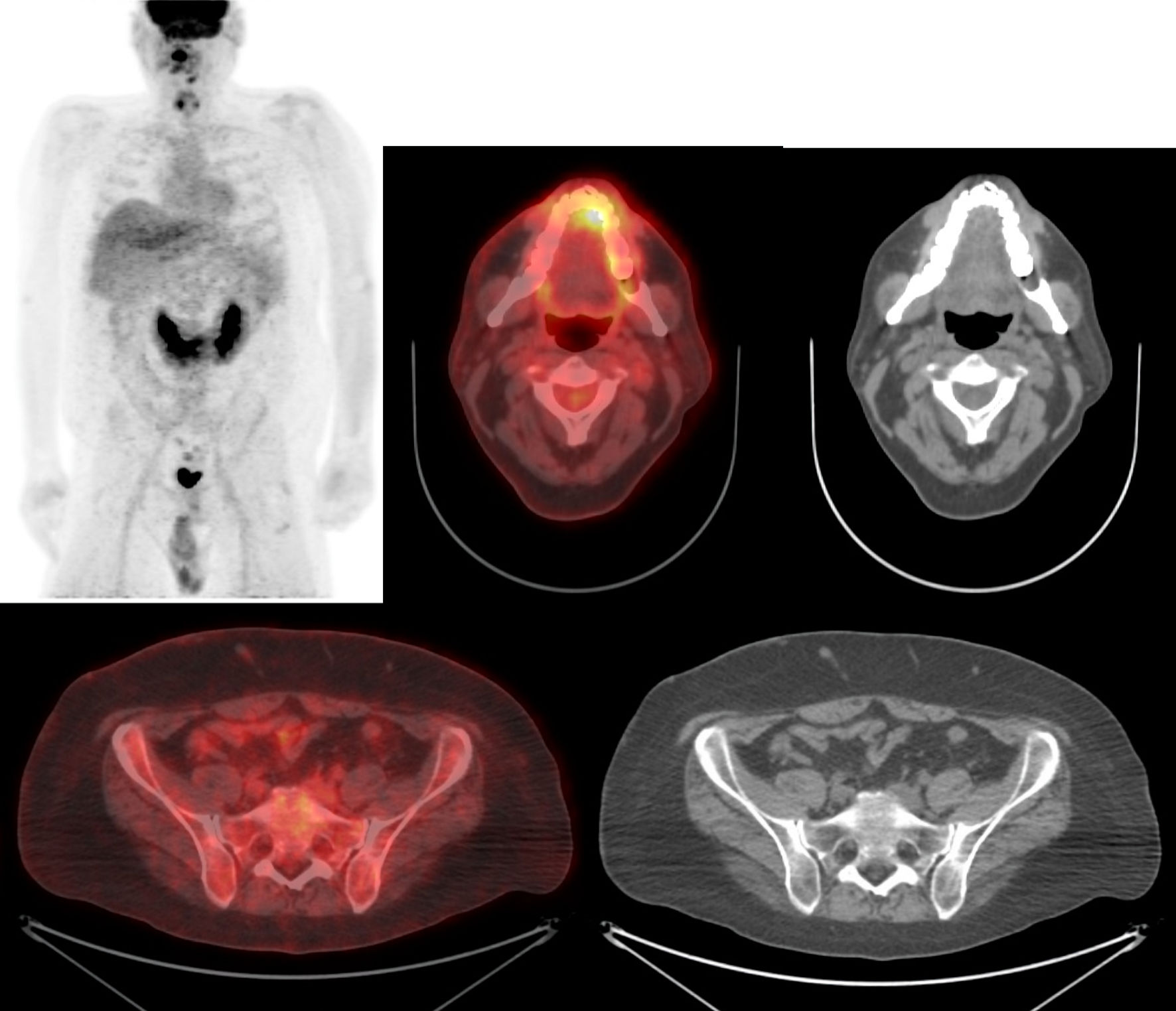

Three weeks after completing chemotherapy, the patient underwent a myeloablative fludarabine busulfan 12.8 mg/kg haploidentical-related 4/8 allogeneic peripheral blood stem cell transplantation with post-transplant cyclophosphamide, sirolimus, and mycophenolate mofetil graft-vs-host disease (GVHD) prophylaxis. He achieved complete donor chimerism of 100% by day 30. Immunosuppression was tapered off by day 70 to promote the graft-versus-lymphoma effect. PET-CT at day 100 post-transplant showed CR (Fig. 4). Bone marrow biopsy showed no lymphoma. He had no acute or chronic GVHD. The patient remains in CR per Lugano criteria 1 year post-transplant at the time of this writing [11].

Click for large image | Figure 4. Complete remission positron emission tomography-computed tomography (PET-CT) scan 3 months post-transplant. Maximum intensity projection (MIP) with fused PET-CT images and corresponding CT images at the C2 and S1 vertebral levels. |

Immunohistochemistry

Immunohistochemistry for phosphorylated AKT was performed in an autostainer on 5-µm sections from a 10% formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded lymphoma specimen. Novacastra liquid mouse monoclonal antibody (NCL-L-Akt-Phos, Clone LP18, Leica Biosystems, UK), an IgG2b antibody with specificity to human AKT phosphorylated at serine 473, was used at a dilution of 1:50 for the qualitative assessment of phosphorylated AKT.

| Discussion | ▴Top |

Induction multiagent chemotherapy can cure 70% of adult BL patients [3]. For the remaining patients, the majority will relapse either during induction chemotherapy or within 6 months after initial CR, as in our patient. No standard therapy exists for this life-threatening presentation, with a response rate to salvage chemotherapy of 0% and a median survival of 6 weeks [4].

Copanlisib is no longer available in the United States after its withdrawal from the market for relapsed follicular lymphoma. However, targeting B-cell receptor signaling via the PI3K/AKT pathway with copanlisib should not be abandoned in BL as it is a promising approach, as shown in this report.

Despite our patient’s early relapse after induction chemotherapy with DA-EPOCH-R, the addition of copanlisib to DA-EPOCH-R, the pre-existing chemotherapeutic regimen, lead to a complete response. This outcome underscores the potential of combining PI3K inhibitors with chemotherapy in BL to overcome chemoresistance, as shown in preclinical studies [8, 9]. BL cell lines resistant to rituximab-chemotherapy showed increased phosphorylation of AKT, as in our patient (Fig. 2b), and inhibition of PI3K resulted in decreased phosphorylation of AKT and in vitro anti-lymphoma activity [8, 9]. The patient’s sustained CR after consolidation with allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation attests to the power of the immune graft-versus-lymphoma effect in chemoresistant BL.

The clinical studies that led to the approval of anti-CD19 chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy for non-Hodgkin lymphoma did not include relapsed or refractory BL patients. CAR T-cell therapy was evaluated in a real-world multicenter retrospective study of 24 relapsed or refractory adult BL patients with a median age of 37 (range 21 - 68) [12]. Patients received commercial CAR T-cell products: axicabtagene ciloleucel (n = 16), tisagenlecleucel (n = 4), lisocabtagene maraleucel (n = 3), or brexucabtagene autoleucel (brexu-cel) (n = 1). Two patients had grade ≥ 3 cytokine release syndrome (CRS). Five patients had grade ≥ 3 immune effector cell-associated neurotoxicity syndrome (ICANS). One-month mortality was 20.8%, including a patient who succumbed to grade 4 ICANS. One month after CAR T-cell infusion, CR was 58.3%, but the responses were not durable. The median OS was 7.1 months (95% confidence interval (CI): 1.9 - 12.9), and the median PFS was 3.1 months (95% CI: 0.9 - 7.9). A prospective study, ZUMA-25, is evaluating brexu-cel in rare B-cell malignancies, including BL. However, CAR T-cell therapy for BL is limited by apheresis and manufacturing time in this highly aggressive lymphoma. There is a lack of durable response with the current commercial CAR T-cell products in relapsed or refractory adult BL patients.

Allogeneic stem cell transplantation can provide durable responses [13, 14]. The Center for International Blood and Marrow Transplant Research (CIBMTR) reported a 5-year OS rate of 30% in relapsed or refractory BL patients who achieved a second CR after salvage chemotherapy, compared to 12% for those not in CR before allogeneic stem cell transplant. The non-relapse mortality was 30%. However, mortality and relapses occurred mainly in the first year, after which there was a plateau on the survival curve, indicating the curative potential of allogeneic stem cell transplantation [14]. This CIBMTR study was conducted between 1985 and 2007, preceding post-transplant cyclophosphamide GVHD prophylaxis. Transplantation-related death has fallen in the modern era due to improvements in GVHD prophylaxis and better supportive care. In a study conducted between 2019 and 2021 comparing post-transplant cyclophosphamide-tacrolimus-mycophenolate mofetil to traditional methotrexate-tacrolimus GVHD prophylaxis, the 1-year transplantation-related death with post-transplant cyclophosphamide was 12.3% versus 17.2% [15]. Moreover, at 1 year, the adjusted GVHD-free, relapse-free survival was 52.7% (95% CI: 45.8 - 59.2) with post-transplant cyclophosphamide prophylaxis versus 34.9% (95% CI: 28.6 - 41.3) with methotrexate prophylaxis. With post-transplant cyclophosphamide prophylaxis, there is less severe acute or chronic GVHD and a higher incidence of immunosuppression-free survival at 1 year, as in our patient [15].

Conclusions

Relapsed or refractory BL in adults is a life-threatening disease for which there is no standard therapy [16]. Due to the rapidly progressing lymphoma, most patients succumb to their disease before being able to receive a potentially curative allogeneic stem cell transplant. A promising approach is to add a novel targeted agent, such as the PI3K inhibitor copanlisib, to chemotherapy to overcome chemoresistance and achieve effective cytoreduction, allowing consolidation with allogeneic stem cell transplantation to achieve durable remission, as in our patient. Further research and consideration of this treatment strategy are needed to improve the outcomes of relapsed BL patients.

Acknowledgments

None to declare.

Financial Disclosure

None to declare.

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from the patient to publish this report and all images.

Author Contributions

All authors collected the data. BW wrote the manuscript. RJ and JL prepared the figures. All authors edited the article and approved the manuscript.

Data Availability

The authors declare that data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article.

| References | ▴Top |

- Teras LR, DeSantis CE, Cerhan JR, Morton LM, Jemal A, Flowers CR. 2016 US lymphoid malignancy statistics by World Health Organization subtypes. CA Cancer J Clin. 2016;66(6):443-459.

doi pubmed - Satou A, Asano N, Nakazawa A, Osumi T, Tsurusawa M, Ishiguro A, Elsayed AA, et al. Epstein-Barr virus (EBV)-positive sporadic burkitt lymphoma: an age-related lymphoproliferative disorder? Am J Surg Pathol. 2015;39(2):227-235.

doi pubmed - Evens AM, Danilov A, Jagadeesh D, Sperling A, Kim SH, Vaca R, Wei C, et al. Burkitt lymphoma in the modern era: real-world outcomes and prognostication across 30 US cancer centers. Blood. 2021;137(3):374-386.

doi pubmed - Short NJ, Kantarjian HM, Ko H, Khoury JD, Ravandi F, Thomas DA, Garcia-Manero G, et al. Outcomes of adults with relapsed or refractory Burkitt and high-grade B-cell leukemia/lymphoma. Am J Hematol. 2017;92(6):E114-E117.

doi pubmed - Schmitz R, Ceribelli M, Pittaluga S, Wright G, Staudt LM. Oncogenic mechanisms in Burkitt lymphoma. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2014;4(2):a014282.

doi pubmed - Love C, Sun Z, Jima D, Li G, Zhang J, Miles R, Richards KL, et al. The genetic landscape of mutations in Burkitt lymphoma. Nat Genet. 2012;44(12):1321-1325.

doi pubmed - Panea RI, Love CL, Shingleton JR, Reddy A, Bailey JA, Moormann AM, Otieno JA, et al. The whole-genome landscape of Burkitt lymphoma subtypes. Blood. 2019;134(19):1598-1607.

doi pubmed - Frys S, Czuczman NM, Mavis C, Rolland DC, Lim MS, Tiwari A, Cairo MS, et al. Deregulation of the PI3K/Akt signal transduction pathway is associated with the development of chemotherapy resistance and can be effectively targeted to improve chemoresponsiveness in Burkitt lymphoma pre-clinical models. Blood. 2014;124:1769.

- Bhatti M, Ippolito T, Mavis C, Gu J, Cairo MS, Lim MS, Hernandez-Ilizaliturri F, et al. Pre-clinical activity of targeting the PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway in Burkitt lymphoma. Oncotarget. 2018;9(31):21820-21830.

doi pubmed - Shan KS, Bonano-Rios A, Theik NWY, Hussein A, Blaya M. Molecular targeting of the Phosphoinositide-3-Protein Kinase (PI3K) pathway across various cancers. Int J Mol Sci. 2024;25(4):1973.

doi pubmed - Cheson BD, Ansell S, Schwartz L, Gordon LI, Advani R, Jacene HA, Hoos A, et al. Refinement of the Lugano Classification lymphoma response criteria in the era of immunomodulatory therapy. Blood. 2016;128(21):2489-2496.

doi pubmed - Samples L, Sadrzadeh H, Frigault MJ, Jacobson CA, Hamadani M, Gurumurthi A, Strati P, et al. Outcomes among adult recipients of CAR T-cell therapy for Burkitt lymphoma. Blood. 2025.

doi pubmed - Sweetenham JW, Pearce R, Taghipour G, Blaise D, Gisselbrecht C, Goldstone AH. Adult Burkitt's and Burkitt-like non-Hodgkin's lymphoma—outcome for patients treated with high-dose therapy and autologous stem-cell transplantation in first remission or at relapse: results from the European Group for Blood and Marrow Transplantation. J Clin Oncol. 1996;14(9):2465-2472.

doi pubmed - Maramattom LV, Hari PN, Burns LJ, Carreras J, Arcese W, Cairo MS, Costa LJ, et al. Autologous and allogeneic transplantation for burkitt lymphoma outcomes and changes in utilization: a report from the center for international blood and marrow transplant research. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2013;19(2):173-179.

doi pubmed - Bolanos-Meade J, Hamadani M, Wu J, Al Malki MM, Martens MJ, Runaas L, Elmariah H, et al. Post-transplantation cyclophosphamide-based graft-versus-host disease prophylaxis. N Engl J Med. 2023;388(25):2338-2348.

doi pubmed - Malfona F, Testi AM, Chiaretti S, Moleti ML. Refractory burkitt lymphoma: diagnosis and interventional strategies. Blood Lymphat Cancer. 2024;14:1-15.

doi pubmed

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial 4.0 International License, which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Journal of Hematology is published by Elmer Press Inc.