| Journal of Hematology, ISSN 1927-1212 print, 1927-1220 online, Open Access |

| Article copyright, the authors; Journal compilation copyright, J Hematol and Elmer Press Inc |

| Journal website https://jh.elmerpub.com |

Original Article

Volume 14, Number 1, February 2025, pages 14-19

Low Rate of Central Nervous System Relapse of Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma Despite Limited Use of Intrathecal Prophylaxis

Aamer Aleema, b, Farjah Algahtania, Musa Alzahrania, Ahmed Jamala, Khalid AlSaleha, Sarah Sewaralthahaba, Fatimah Alshalatia, Omar Alorainia, Mohammed Almozinia, Abdulaziz Abdulkarima, Omar Alayeda, Ghazi Alotaibia

aDivision of Hematology/Oncology (Oncology Center), Department of Medicine, College of Medicine, King Khalid University Hospital, King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia

bCorresponding Author: Aamer Aleem, Department of Medicine (Hematology/Oncology), College of Medicine, King Khalid University Hospital, King Saud University, Riyadh 11472, Saudi Arabia

Manuscript submitted October 3, 2024, accepted November 30, 2024, published online December 31, 2024

Short title: Low Rate of CNS Relapse in DLBCL

doi: https://doi.org/10.14740/jh1363

| Abstract | ▴Top |

Background: The incidence of central nervous system (CNS) relapse in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) varies, and the optimum strategy of CNS prophylaxis remains to be defined. We aimed to evaluate the incidence of CNS relapse in DLBCL patients and the role of CNS prophylaxis.

Methods: Data on patients diagnosed with DLBCL at our institution from January 2011 to June 2019 were retrospectively collected from the charts and computerized hospital information system for patient demographics, lymphoma stage at diagnosis, CNS international prognostic index (IPI) scores, extra-nodal sites, chemotherapy type, CNS prophylaxis, and CNS relapse. CNS prophylaxis comprised intrathecal (IT) chemotherapy and was administered based on the presence of high-risk features. Patients with primary CNS lymphoma and CNS involvement at diagnosis were excluded.

Results: Of 101 patients, 58 (57.5%) were males with a median age of 56 (range: 16 - 87) years. Ann Arbor stages of I - IV were confirmed in nine, 21, 17, and 50 patients, respectively. The lung was the most common extranodal site involved (27, 26.7%). Twenty-five (24.75%) patients had a high-risk CNS-IPI score. Ninety-three percent of patients received R-CHOP (rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone) chemotherapy. Sixteen patients received CNS prophylaxis as IT methotrexate (± cytarabine and hydrocortisone). Despite high-risk CNS-IPI scores, nine (36%) patients did not receive CNS prophylaxis. After a median follow-up of 36 (range: 4 - 114) months, two patients with high-risk CNS-IPI score developed CNS relapse and died shortly.

Conclusions: CNS relapse of DLBCL was uncommon in this patient population. Low incidence of CNS relapse despite limited use of IT prophylaxis may suggest adequacy of IT prophylaxis in these patients.

Keywords: Central nervous system; Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma; CNS relapse; Prophylaxis

| Introduction | ▴Top |

Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) is the most common subtype of non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL), accounting for 30-58% of all NHL cases [1, 2]. The outcome of patients with DLBCL has improved with the addition of rituximab to the CHOP (cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisolone) chemotherapy, but a significant number of patients continue to suffer relapse despite the initial complete response [3, 4].

After the initial therapy, around 5% of patients with DLBCL experience central nervous system (CNS) relapse, which is associated with a very poor prognosis and median survival of around 4 months [5, 6]. The incidence of CNS relapse varies from 2% to more than 10% in patients with multiple risk factors [5-8]; however, the CNS relapse risk has been reported to be lower in some studies in the rituximab era [8-11].

CNS prophylaxis strategies to prevent CNS relapse in DLBCL include intrathecal (IT) chemotherapy and systemic agents with CNS penetration, such as high-dose methotrexate (HD-MTX). Both IT chemotherapy and HD-MTX are widely used in practice. Currently, there is no consensus on the standard of care for CNS prophylaxis.

Systemic chemotherapy has often been considered a preferred strategy for CNS prophylaxis in DLBCL, particularly for parenchymal disease, as IT chemotherapy does not penetrate the brain parenchyma adequately. Therefore, IT chemotherapy has been considered insufficient in preventing parenchymal CNS recurrences [7, 12, 13]. However, the superior efficacy of systemic CNS prophylaxis remains debatable [12-15].

Given the reported variability in CNS relapse incidence across studies in DLBCL patients [5, 7-11, 16], it is important to examine this risk in different populations to develop optimal prophylaxis strategies. We conducted this study to evaluate CNS relapse and the role of CNS prophylaxis in DLBCL patients treated at our institution.

| Materials and Methods | ▴Top |

DLBCL patients diagnosed and treated at King Khalid University Hospital, Riyadh, from January 2011 to June 2019 were retrospectively analyzed. Data were collected from the computerized hospital information system and patients’ files. Variables studied included age, gender and lymphoma stage at diagnosis, CNS international prognostic index (CNS-IPI) score, site(s) of extra nodal involvement, type of systemic chemotherapy, CNS prophylaxis received, and the rate of CNS relapse. CNS prophylaxis was administered based on the presence of high-risk features, such as ≥ two extranodal sites, involvement of bone marrow (BM), testes, kidneys, nasopharynx, and paranasal sinuses.

Patients older than 16 years and with a minimum follow-up of 3 months were included. Patients with primary CNS lymphoma and presence of CNS involvement at diagnosis were excluded. Patients who received supportive care only and did not receive any systemic therapy (usually elderly patients with poor performance status, rendered unfit for any systemic therapy), were also excluded.

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board and was conducted in compliance with the ethical standards of the responsible institution on human subjects as well as with the Helsinki Declaration.

| Results | ▴Top |

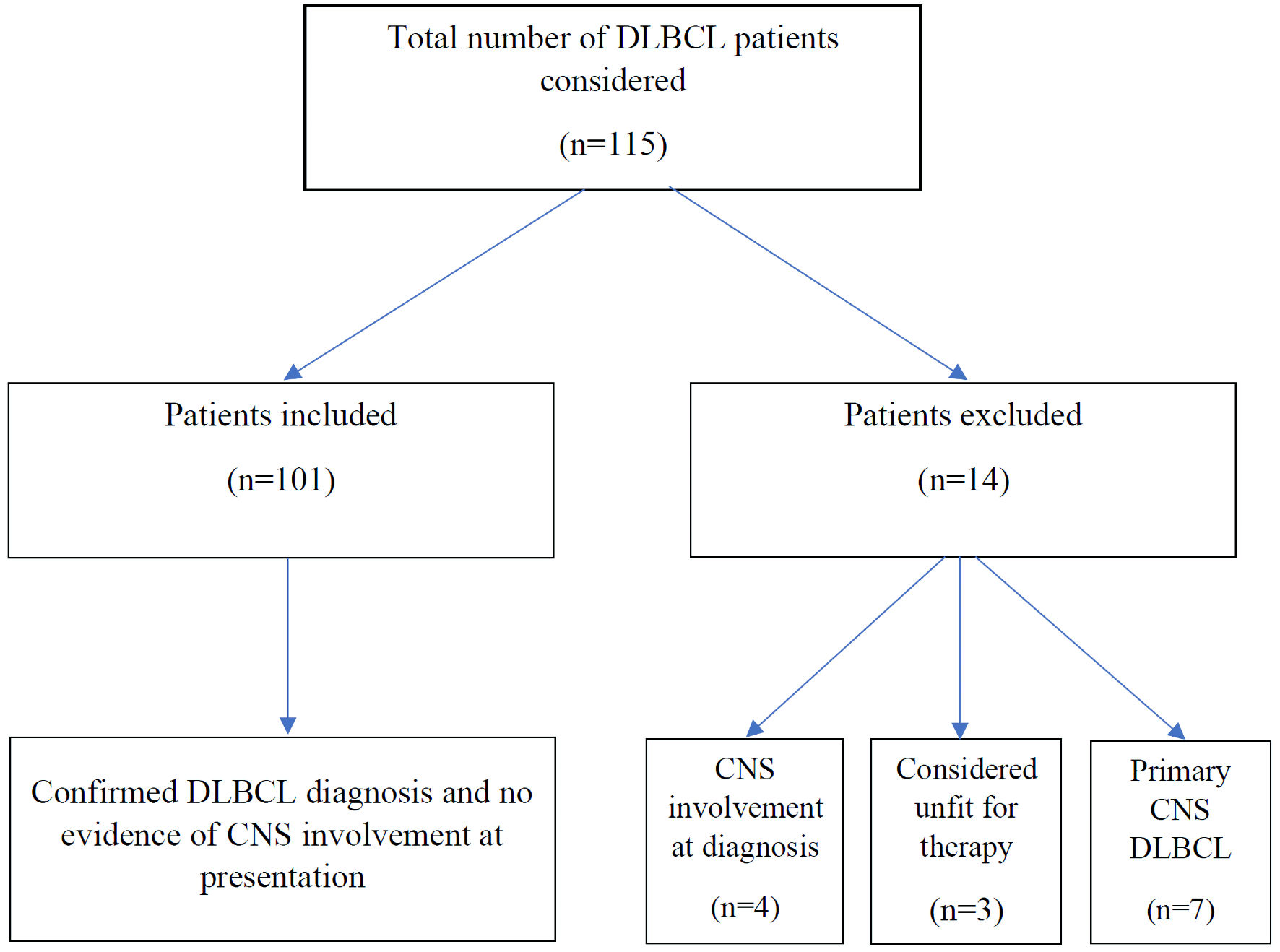

A total of 115 patients were diagnosed with DLBCL during the study period, and 101 patients fulfilled the inclusion criteria. Patient inclusions and exclusions are shown in Figure 1. There was a male preponderance, with 58 (57.5%) males and 43 (42.5%) females, and with a median age of 56 (range: 16 - 87) years. The majority of the patients had advanced stage disease, with Ann Arbor stage of III and IV present in 17, and 50 patients, respectively (Table 1). The lung was the most common extranodal site, involved in 27 (26.7%) patients, followed by liver and BM involvement in 20 (19.8%) patients each. Other extranodal sites involved included gastrointestinal tract, kidneys, breast, testis, and adrenals. The details of involvement of extranodal sites are shown in Table 2. Twenty-five (24.75%) patients had high-risk CNS-IPI scores, 44 (43.5%) had intermediate-risk scores, and 32 (31.7%) patients had low-risk scores. Ninety-four (93%) patients received R-CHOP (rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone) chemotherapy regimen, while the rest received other types of chemotherapy, mostly a milder regimen like R-CVP (rituximab, cyclophosphamide, vincristine, and prednisone), because of comorbidities and poor performance status.

Click for large image | Figure 1. Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) cases and the patient inclusions and exclusions. CNS: central nervous system. |

Click to view | Table 1. Patients’ Characteristics |

Click to view | Table 2. Extranodal Sites Involved |

Characteristics of the patients with high-risk CNS-IPI are shown in Table 3. Median age of the high-risk group was 65 years, and 16 (64%) patients were males. All high-risk patients had stage IV disease except two patients who had stage III disease. After a median follow-up of 28 months for the high-risk group, 14 (56%) patients were still alive at the last follow-up.

Click to view | Table 3. Characteristics of 25 Patients With High-Risk CNS-IPI |

Of the 25 high risk patients, 16 (64%) patients received CNS prophylaxis, usually based on the involvement of high-risk extranodal sites. CNS prophylaxis was IT-MTX (± cytarabine and hydrocortisone) in all patients. Patients who received IT prophylaxis received a median of three IT chemotherapy injections (range: 1 - 6). Despite the high-risk CNS-IPI scores or involvement of high-risk organs like kidneys, adrenals, testes, and/or BM, nine of 25 (36%) patients did not receive CNS prophylaxis based on individual physician preference.

After a median follow-up of 36 months (range: 4 - 114) for the whole group, two (2%) patients developed CNS relapse and died shortly after this diagnosis. Both the patients with CNS relapse had a high-risk CNS-IPI score, with the involvement of one or more high-risk extranodal sites. The CNS relapse was leptomeningeal in one patient and parenchymal in the second patient. The diagnosis of CNS relapse was made on imaging and cerebrospinal fluid examination in the first patient with leptomeningeal relapse, while the diagnosis of CNS relapse was made on imaging only in the patient with parenchymal relapse. Both the patients with CNS relapse had received R-CHOP regimen as systemic therapy and did not receive any CNS prophylaxis.

| Discussion | ▴Top |

CNS relapse of DLBCL is a devastating event occurring in around 5% of patients treated with R-CHOP chemotherapy regimen. However, according to the CNS-IPI score, the risk of CNS relapse varies depending upon the risk factors present in an individual patient. High-risk patients with multiple risk factors may exhibit a relapse risk as high as 30% [17]. One large study in the pre-rituximab era reported a low risk of CNS relapse, with most relapses occurring early during chemotherapy or soon after it, suggesting the presence of subclinical disease at diagnosis [5].

The international CNS-IPI score remains a robust risk stratification tool [18]; however, it might not capture high-risk patients with limited-stage extra-nodal lymphomas, such as testicular and breast DLBCL, associated with a high risk of CNS relapse [19, 20]. More recently, the addition of other factors, such as the cell of origin and MYC/BCL2 expression, has further refined the CNS-IPI to improve the characterization of high-risk patients [21].

The impact of rituximab on CNS relapse in DLBCL remains debatable. Although several studies have shown that CNS relapse of DLBCL was less frequent in patients treated with rituximab-containing regimens [8-11], other studies were unable to replicate this benefit [6]. A meta-analysis examining the impact of rituximab on CNS relapse of DLBCL showed a lower incidence of CNS relapse in the rituximab era [22]. Moreover, CNS relapse is variable in different published studies, and it was so infrequent in some patient populations that the authors questioned the use of routine CNS prophylaxis [5, 11].

Reduction in the CNS relapse of DLBCL in the rituximab era has been attributed to improved control of the systemic disease. Rituximab has limited penetration of the blood-brain barrier, and rituximab concentration in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) after intravenous administration was found to reach only 0.1% of the serum concentration [23]. Whether this limited concentration of rituximab in the CSF contributes to the reduced CNS relapse of DLBCL is not certain.

The strategies for CNS prophylaxis to prevent CNS relapse include IT chemotherapy and systemic therapy with CNS penetration such as HD-MTX. Both IT chemotherapy and systemic HD-MTX are widely used in clinical practice. Systemic chemotherapy has been recommended for CNS prophylaxis of DLBCL, especially for parenchymal disease, as IT chemotherapy does not adequately penetrate the brain parenchyma and is considered insufficient in preventing parenchymal CNS recurrences [7, 12, 13]. Even though systemic CNS prophylaxis with HD-MTX has been practiced as a preferred strategy, its efficacy remains unclear [12-15].

Some recent studies have cast doubt on the efficacy of HD-MTX and showed that HD-MTX was ineffective in preventing CNS relapse [12, 14, 15]. One large study of DLBCL from 21 US centers with 1,162 patients did not find any difference in CNS relapse with IT or systemic prophylaxis [24]. Another study showed the benefit of HD-MTX in improving progression free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) in high-risk DLBCL patients but no benefit in preventing CNS relapse [25]. Interestingly, one study reported a higher incidence of CNS relapse in a group of high-risk DLBCL patients treated with systemic HD-MTX as compared to those who did not receive prophylaxis [26]. Gonzalez-Barca et al used liposomal cytarabine for CNS prophylaxis and interestingly, there were no CNS relapses in these patients [27]. However, liposomal cytarabine for CNS prophylaxis has not been widely adopted in practice.

Current study showed that the risk of CNS relapse was low in our DLBCL patients treated with rituximab-based regimens despite some high-risk patients not receiving any prophylaxis. Although challenging to explain the factor(s) associated with low relapse rates in our patients, it may be related to a possible protective effect of rituximab and/or other factors. Some other studies in the pre- and post-rituximab era have reported similar results [5, 9, 11, 22], and because of the low rate of CNS recurrence and lack of prophylaxis-associated survival benefit, some investigators have called into question the practice of CNS prophylaxis in the rituximab era [11]. Although prophylaxis is needed in high-risk patients, emerging data cast doubt on the benefit of systemic therapy with HD-MTX, as CNS prophylaxis coupled with its added toxicity, possibly delaying primary lymphoma treatment, and potential inferior outcome of systemic lymphoma.

Currently, it is not clear which patients should receive HD-MTX or just IT chemotherapy. Some very high-risk patients might benefit from systemic therapy; nonetheless, further studies are needed stratifying patients according to the number of CNS relapse risk factors and incorporating novel agents for prophylaxis [28]. Until such evidence may become available, it seems prudent that CNS prophylaxis should be practiced according to local experience and results. As the high-risk patients are at increased risk of CNS relapse, proper selection criteria should be employed for administering prophylaxis, with consideration of incorporating molecular diagnostics to improve identifying such patients [12, 13]. Given that CNS relapse is associated with high mortality and lack of effective therapies, the authors believe high-risk patients should continue to receive CNS prophylaxis.

Recently, polatuzumab vedotin has been approved in combination with rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin and prednisone (R-CHP) for adult patients with untreated DLBCL. At present, there are limited data on the use of polatuzumab vedotin and the incidence of CNS relapse in newly diagnosed DLBCL patients. POLARIX trial compared R-CHOP regimen with polatuzumab vedotin in combination with R-CHP (Pola-R-CHP) in previously untreated DLBCL patients [29]. CNS prophylaxis with IT chemotherapy was permitted according to individual institutional practice guidelines. CNS relapse was similar in both groups and reported in 3.0% of patients in the Pola-R-CHP group and 2.7% of patients in the R-CHOP group [29].

Newly emerging data show that chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy can be useful in patients with CNS relapse (secondary CNS involvement) of DLBCL. Epperla et al conducted a multi-center retrospective cohort study and reported high complete remission rates following CAR T-cell therapy for secondary CNS lymphoma in 61 patients, but the responses were not durable with most patients experiencing early relapse and death [30]. Another smaller multi-center study found that CD19 CAR T-cell therapy for patients with LBCL with secondary CNS involvement (28 patients) was safe and resulted in durable responses comparable to patients without CNS involvement [31]. A meta-analysis including 128 patients reported efficacy and safety of CAR T-cell in secondary (n = 98) and primary (n = 30) CNS lymphoma with similar outcomes for patients without CNS involvement [32]. These studies confirm the efficacy of CAR T-cell therapy in patients with CNS relapse of DLBCL, although long-term durability of this approach is not yet established.

Our study has certain limitations which include a retrospective design and smaller number of patients. However, it gives a fair idea of the CNS relapse risk in our patients and may help guide the CNS prophylaxis practice in this DLBCL patient population.

Conclusions

CNS relapse of DLBCL was uncommon in the current study. The low incidence of CNS relapse despite limited use of IT prophylaxis may suggest an overall low risk of CNS relapse and adequacy of IT prophylaxis for high-risk patients in this patient population. Further studies are needed stratifying patients according to number of risk factors and incorporating novel target agents that could penetrate CNS.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the College of Medicine Research Center, Deanship of Scientific Research, King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Financial Disclosure

None to declare.

Conflict of Interest

This study was presented as an Abstract at XIII Eurasian Hematology Oncology Congress held in Istanbul in October 2022.

Informed Consent

The requirement for written informed consent was waived due to the retrospective nature of the study.

Author Contributions

Concept of the study: AA. Manuscript writing: AA, GAO. Data collection and analysis: AA, OAO, MAM, AbAb, OAA, GAO. Patient management: AA, FAG, MAZ, AJ, KAS, SS, FAS, GAO. Critical review of manuscript: AA, FAG, MAZ, AJ, KAS, SS, FAS, OAO, MAM, AbAb, OAA, GAO.

Data Availability

The data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

| References | ▴Top |

- Alaggio R, Amador C, Anagnostopoulos I, Attygalle AD, Araujo IBO, Berti E, Bhagat G, et al. The 5th edition of the World Health Organization Classification of Haematolymphoid Tumours: Lymphoid Neoplasms. Leukemia. 2022;36(7):1720-1748.

doi pubmed - Martelli M, Ferreri AJ, Agostinelli C, Di Rocco A, Pfreundschuh M, Pileri SA. Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2013;87(2):146-171.

doi pubmed - Borchmann P, Heger JM, Mahlich J, Papadimitrious MS, Riou S, Werner B. Survival outcomes of patients newly diagnosed with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: real-world evidence from a German claims database. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2023;149(10):7091-7101.

doi pubmed - Pfreundschuh M, Trumper L, Osterborg A, Pettengell R, Trneny M, Imrie K, Ma D, et al. CHOP-like chemotherapy plus rituximab versus CHOP-like chemotherapy alone in young patients with good-prognosis diffuse large-B-cell lymphoma: a randomised controlled trial by the MabThera International Trial (MInT) Group. Lancet Oncol. 2006;7(5):379-391.

doi pubmed - Bernstein SH, Unger JM, Leblanc M, Friedberg J, Miller TP, Fisher RI. Natural history of CNS relapse in patients with aggressive non-Hodgkin's lymphoma: a 20-year follow-up analysis of SWOG 8516 — the Southwest Oncology Group. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(1):114-119.

doi pubmed - Ferreri AJ, Bruno-Ventre M, Donadoni G, Ponzoni M, Citterio G, Foppoli M, Vignati A, et al. Risk-tailored CNS prophylaxis in a mono-institutional series of 200 patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma treated in the rituximab era. Br J Haematol. 2015;168(5):654-662.

doi pubmed - Villa D, Connors JM, Shenkier TN, Gascoyne RD, Sehn LH, Savage KJ. Incidence and risk factors for central nervous system relapse in patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: the impact of the addition of rituximab to CHOP chemotherapy. Ann Oncol. 2010;21(5):1046-1052.

doi pubmed - Kuitunen H, Kaprio E, Karihtala P, Makkonen V, Kauppila S, Haapasaari KM, Kuusisto M, et al. Impact of central nervous system (CNS) prophylaxis on the incidence of CNS relapse in patients with high-risk diffuse large B cell/follicular grade 3B lymphoma. Ann Hematol. 2020;99(8):1823-1831.

doi pubmed - Gleeson M, Counsell N, Cunningham D, Chadwick N, Lawrie A, Hawkes EA, McMillan A, et al. Central nervous system relapse of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma in the rituximab era: results of the UK NCRI R-CHOP-14 versus 21 trial. Ann Oncol. 2017;28(10):2511-2516.

doi pubmed - Guirguis HR, Cheung MC, Mahrous M, Piliotis E, Berinstein N, Imrie KR, Zhang L, et al. Impact of central nervous system (CNS) prophylaxis on the incidence and risk factors for CNS relapse in patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma treated in the rituximab era: a single centre experience and review of the literature. Br J Haematol. 2012;159(1):39-49.

doi pubmed - Kumar A, Vanderplas A, LaCasce AS, Rodriguez MA, Crosby AL, Lepisto E, Czuczman MS, et al. Lack of benefit of central nervous system prophylaxis for diffuse large B-cell lymphoma in the rituximab era: findings from a large national database. Cancer. 2012;118(11):2944-2951.

doi pubmed - Bobillo S, Khwaja J, Ferreri AJM, Cwynarski K. Prevention and management of secondary central nervous system lymphoma. Haematologica. 2023;108(3):673-689.

doi pubmed - Wilson MR, Bobillo S, Cwynarski K. CNS prophylaxis in aggressive B-cell lymphoma. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2022;2022(1):138-145.

doi pubmed - Lewis KL, Jakobsen LH, Villa D, Bobillo S, Smedby KE, Savage KJ, Eyre TA, et al. High-dose methotrexate is not associated with reduction in CNS relapse in patients with aggressive B-cell lymphoma: an international retrospective study of 2300 high-risk patients. Blood. 2021;138(supplement 1):181.

- Puckrin R, El Darsa H, Ghosh S, Peters A, Owen C, Stewart D. Ineffectiveness of high-dose methotrexate for prevention of CNS relapse in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Am J Hematol. 2021;96(7):764-771.

doi pubmed - Feugier P, Virion JM, Tilly H, Haioun C, Marit G, Macro M, Bordessoule D, et al. Incidence and risk factors for central nervous system occurrence in elderly patients with diffuse large-B-cell lymphoma: influence of rituximab. Ann Oncol. 2004;15(1):129-133.

doi pubmed - Calimeri T, Lopedote P, Ferreri AJ. Risk stratification and management algorithms for patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma and CNS involvement. Ann Lymphoma. 2019;3(7):1-18.

- Schmitz N, Zeynalova S, Nickelsen M, Kansara R, Villa D, Sehn LH, Glass B, et al. CNS International Prognostic Index: a risk model for CNS relapse in patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma treated with R-CHOP. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(26):3150-3156.

doi pubmed - Hosein PJ, Maragulia JC, Salzberg MP, Press OW, Habermann TM, Vose JM, Bast M, et al. A multicentre study of primary breast diffuse large B-cell lymphoma in the rituximab era. Br J Haematol. 2014;165(3):358-363.

doi pubmed - Kridel R, Telio D, Villa D, Sehn LH, Gerrie AS, Shenkier T, Klasa R, et al. Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma with testicular involvement: outcome and risk of CNS relapse in the rituximab era. Br J Haematol. 2017;176(2):210-221.

doi pubmed - Klanova M, Sehn LH, Bence-Bruckler I, Cavallo F, Jin J, Martelli M, Stewart D, et al. Integration of cell of origin into the clinical CNS International Prognostic Index improves CNS relapse prediction in DLBCL. Blood. 2019;133(9):919-926.

doi pubmed - Zhang J, Chen B, Xu X. Impact of rituximab on incidence of and risk factors for central nervous system relapse in patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Leuk Lymphoma. 2014;55(3):509-514.

doi pubmed - Rubenstein JL, Combs D, Rosenberg J, Levy A, McDermott M, Damon L, Ignoffo R, et al. Rituximab therapy for CNS lymphomas: targeting the leptomeningeal compartment. Blood. 2003;101(2):466-468.

doi pubmed - Orellana-Noia VM, Reed DR, McCook AA, Sen JM, Barlow CM, Malecek MK, Watkins M, et al. Single-route CNS prophylaxis for aggressive non-Hodgkin lymphomas: real-world outcomes from 21 US academic institutions. Blood. 2022;139(3):413-423.

doi pubmed - Goldschmidt N, Horowitz NA, Heffes V, Darawshy F, Mashiach T, Shaulov A, Gatt ME, et al. Addition of high-dose methotrexate to standard treatment for patients with high-risk diffuse large B-cell lymphoma contributes to improved freedom from progression and survival but does not prevent central nervous system relapse. Leuk Lymphoma. 2019;60(8):1890-1898.

doi pubmed - Lee K, Yoon DH, Hong JY, Kim S, Lee K, Kang EH, Huh J, et al. Systemic HD-MTX for CNS prophylaxis in high-risk DLBCL patients: a prospectively collected, single-center cohort analysis. Int J Hematol. 2019;110(1):86-94.

doi pubmed - Gonzalez-Barca E, Canales M, Salar A, Ferreiro-Martinez JJ, Ferrer-Bordes S, Garcia-Marco JA, Sanchez-Blanco JJ, et al. Central nervous system prophylaxis with intrathecal liposomal cytarabine in a subset of high-risk patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma receiving first line systemic therapy in a prospective trial. Ann Hematol. 2016;95(6):893-899.

doi pubmed - Lin Z, Chen X, Liu L, Zeng H, Li Z, Xu B. The role of central nervous system (CNS) prophylaxis in preventing DLBCL patients from CNS relapse: A network meta-analysis. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2022;176:103756.

doi pubmed - Tilly H, Morschhauser F, Sehn LH, Friedberg JW, Trneny M, Sharman JP, Herbaux C, et al. Polatuzumab vedotin in previously untreated diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 2022;386(4):351-363.

doi pubmed - Epperla N, Feng L, Shah NN, Fitzgerald L, Shah H, Stephens DM, Lee CJ, et al. Outcomes of patients with secondary central nervous system lymphoma following CAR T-cell therapy: a multicenter cohort study. J Hematol Oncol. 2023;16(1):111.

doi pubmed - Ayuk F, Gagelmann N, von Tresckow B, Wulf G, Rejeski K, Stelljes M, Penack O, et al. Real-world results of CAR T-cell therapy for large B-cell lymphoma with CNS involvement: a GLA/DRST study. Blood Adv. 2023;7(18):5316-5319.

doi pubmed - Cook MR, Dorris CS, Makambi KH, Luo Y, Munshi PN, Donato M, Rowley S, et al. Toxicity and efficacy of CAR T-cell therapy in primary and secondary CNS lymphoma: a meta-analysis of 128 patients. Blood Adv. 2023;7(1):32-39.

doi pubmed

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial 4.0 International License, which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Journal of Hematology is published by Elmer Press Inc.