| Journal of Hematology, ISSN 1927-1212 print, 1927-1220 online, Open Access |

| Article copyright, the authors; Journal compilation copyright, J Hematol and Elmer Press Inc |

| Journal website https://jh.elmerpub.com |

Original Article

Volume 14, Number 6, December 2025, pages 307-313

Outcomes of Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation Following the Use of Blinatumomab in Pediatric Relapsed B-Cell Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia: A Single-Center Experience

Aditi Tulsiyana, Anuj Singha , Nita Radhakrishnana, b

, Hari Gairea, Sudipto Bhattacharyaa, Anukriti Srivastavaa

aDepartment of Pediatric Hematology Oncology, Post Graduate Institute of Child Health, Noida, Delhi 201303, India

bCorresponding Author: Nita Radhakrishnan, Department of Pediatric Hematology Oncology, Post Graduate Institute of Child Health, Noida, Delhi 201303, India

Manuscript submitted October 25, 2025, accepted December 11, 2025, published online December 30, 2025

Short title: Outcomes of HSCT After Blinatumomab in B-ALL

doi: https://doi.org/10.14740/jh2132

| Abstract | ▴Top |

Background: Relapsed/refractory (R/R) B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (B-ALL) remains associated with poor outcomes in children. Achieving measurable residual disease (MRD) negativity prior to allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) is critical for durable remission. Blinatumomab, a bispecific CD19-CD3 T-cell engager, induces deep remissions with minimal myelosuppression and is increasingly utilized as a bridge to HSCT. We describe our institutional experience with HSCT following blinatumomab-induced remission in pediatric R/R B-ALL.

Methods: This retrospective single-center study included five pediatric patients with R/R B-ALL who received blinatumomab bridging therapy prior to allogeneic HSCT between January 2020 and June 2025. Clinical data included demographics, prior therapies, blinatumomab dosing and duration, MRD status, conditioning regimen, donor source, stem cell dose, engraftment kinetics, donor chimerism, and complications. The endpoints included MRD clearance before HSCT, engraftment kinetics, donor chimerism, viral reactivation, bacterial infections post-transplant, and overall and failure-free survival at last follow-up.

Results: All five patients completed one to two 28-day cycles of blinatumomab and achieved MRD negativity (< 0.01%) prior to HSCT. Donor sources comprised one matched sibling and four haploidentical family donors. The median interval between blinatumomab completion and HSCT was 32 days. Median neutrophil and platelet engraftment occurred on days +12 and +9, respectively. Full donor chimerism was achieved within 1 - 3 months and sustained throughout follow-up. Post-transplant complications included engraftment syndrome (n = 4), cytomegalovirus (CMV) reactivation (n = 4), Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) reactivation (n = 1), Clostridioides difficile enterocolitis (n = 1), and steroid-refractory acute graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) (n = 2). No transplant-related mortality was observed. At a median follow-up of 173 days (range, 52 - 1,015 days), all patients remained alive and in continuous complete remission with no active GVHD.

Conclusions: In this single-center experience from a low-/middle-income country (LMIC), blinatumomab served as an effective bridge to HSCT, enabling MRD-negative remissions with favorable post-transplant outcomes. Viral reactivations and steroid-refractory GVHD were reported, underlining the need for robust surveillance. Broader access to blinatumomab and prospective studies are needed to validate these findings and to evaluate cost-effectiveness in LMICs.

Keywords: Blinatumomab; HSCT in LMICs; Immunotherapy; Relapsed ALL

| Introduction | ▴Top |

Relapsed acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) is a major cause of mortality and morbidity in children with cancer worldwide. The burden of the disease is borne mainly by low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) due to the volume of patients, poor access to supportive care, and novel immunotherapeutic agents that are more efficacious with less toxicity [1]. Overall, relapse occurs in 10-15% of children with ALL treated on contemporary protocols, although the proportion is higher in high-risk groups such as T-lineage ALL, infant ALL, and those with poor response to treatment. Published series from LMICs report event-free survival of around 30-40% in children treated with curative intent, with almost dismal outcomes (2-year EFS < 20%) for very early and early relapses [2]. For low- and intermediate-risk relapses, the outcome is however, better [3, 4].

For children who achieve a second remission, consolidation by hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) from best available donor, strongly predicts better outcomes in high-risk relapses. To achieve this, conventionally, salvage cytotoxic regimens that are highly myelosuppressive are needed, which can be difficult to replicate in LMICs, as supportive care resources including antimicrobials, specialized nursing, and blood component transfusions are limited. This leads to high rates of toxic death and treatment abandonment [2]. Over the years, access to HSCT has improved in India. But access to novel immunotherapeutic agents or cell therapies remains restricted. Immunotherapy can offer deeper remissions with lesser marrow toxicity, reduce supportive care needs, and improve remission rates in patients with chemo-resistant disease as is usually the case in very early and early relapses. The primary barrier to access remains the cost of therapy.

Despite this, there are reports from LMICs describing outcomes of HSCT after second remission using blinatumomab as a bridge to therapy following relapse. We present a single-center case series of five pediatric patients who underwent HSCT at our center; the challenges faced and the outcome and review contemporary literature to contextualize this to feasibility, toxicity, and access challenges in resource-constrained settings [5, 6].

| Materials and Methods | ▴Top |

We report a retrospective observational series of children with B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (B-ALL) who underwent HSCT at our center for very early or early relapse or in late relapse with MRD positive in whom blinatumomab was used as salvage therapy for remission induction. The cohort included consecutive patients ≤ 18 years who underwent HSCT between January 2020 and June 2025. The details of the primary disease, time and risk stratification at relapse, treatment received at relapse, challenges faced at relapse, salvage treatment (chemotherapy and blinatumomab), measurable residual disease (MRD) prior to HSCT, stem cell donor source, dose and time of engraftment, and infection profile in post-transplantation period are reported here. Institutional review board approval for reporting outcome of pediatric cancer was obtained (study protocol number: 2023-10-EM-43). The work was conducted in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible institutional review board and in compliance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Blinatumomab was administered as continuous intravenous infusion via ambulatory or inpatient pump for 28 days (one cycle), at a dose of 5 µg/m2/day for days 1 - 7 followed by 15 µg/m2/day for days 8 - 28. For patients who received blinatumomab at our center (n = 3), infusions were managed by trained nursing staff with protocols for line care, electrolyte monitoring, and neurological observation. Two patients received blinatumomab at another center and were referred to us for HSCT once remission was achieved. MRD was measured by multicolor flow cytometry, with negative report considered as < 0.01% (10-4). Hospital records were reviewed for demographic information, details of disease at initial presentation, challenges faced if any during initial treatment, timing of relapse, risk stratification, treatment received for relapse, dose and duration of blinatumomab, MRD at end of treatment and on follow-up. Details of transplant conditioning and donor details, stem cell dose (CD34+ cells/kg) infused, engraftment kinetics (absolute neutrophil count (ANC) > 500/µL sustained; platelets > 20,000/µL unsupported), donor chimerism at day +30, infectious events, graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) incidence and grade, non-infectious transplant complications, and survival outcomes were also recorded.

HSCT conditioning was decided based on sites of relapse, prior irradiation, and donor source. In case of children who underwent matched family donor HSCT, cyclophosphamide combined with total body irradiation (CyTBI) was used and in haploidentical HSCT, fludarabine-TBI (FluTBI) was used. In one child who had received cranial and testicular irradiation during the first relapse, TBI-free regimen (thiotepa-fludarabine-busulfan) was offered as conditioning for bone marrow transplantation (BMT) after second relapse. A dose of 12 Gy of TBI was given over 4 days with cranial boost of 6 Gy in case of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) involvement at relapse.

The preferred donor was a fully matched sibling or family member (10/10 or 12/12 HLA match). In the absence of such a donor, a haploidentical family member (father preferred or sibling) was chosen provided donor-specific antibodies (DSA) were negative. Matched unrelated donors were not considered, as the additional costs of procurement from the stem cell registries were not covered under government funding and were unaffordable for our patients. In matched donors, a minimum of 5 × 106/kg CD34 stem cells were preferred whereas in haploidentical HSCT, the CD34+ cell dose was calculated with consideration of the CD3+ content of the graft, which was maintained between 2.5 and 3 × 108/kg of recipient body weight.

GVHD prophylaxis was methotrexate with a calcineurin inhibitor for matched sibling transplantations. In case of haploidentical transplant, post-transplant cyclophosphamide (PTCy) was used as per standard protocol. Cyclophosphamide was given at a dose of 50 mg/kg/day intravenously on days +3 and +4 post-HSCT, followed by cyclosporine A (CSA) from day +5, in combination with mycophenolate mofetil (MMF) which was given from day +5 to day +35. CSA was gradually tapered after day +180, to facilitate graft-versus-leukemia (GVL) effect, provided that there is no evidence of active GVHD [7]. Earlier tapering was done in case of difficult viral reactivation or slipping chimerism. Ex vivo T-cell depletion strategy was not used for any. Standard antimicrobial surveillance and pre-emptive treatment were followed for CMV, adenovirus, and EBV infections. Standard nutritional support was provided, with oral, nasogastric, or parenteral routes, individualized according to patient tolerance and clinical condition. After transplantation, bone marrow aspiration for MRD and CSF cytopathology for blasts were usually assessed at days +30, +60, and +90 and if required thereafter [8]. Peripheral blood chimerism was measured on whole blood at day +30, day +60, day +90, and 3 - 6 months thereafter or as clinically indicated [9].

The endpoints included MRD clearance before HSCT, engraftment kinetics, donor chimerism, viral reactivation, bacterial infections post-transplant, overall survival (OS), and failure-free survival (FFS). Statistical analysis was performed using MS Excel or SPSS version 17.0 and Kaplan-Meier survival curves were generated using GraphPad Prism version 9.0.

| Results | ▴Top |

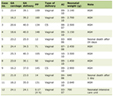

Five patients met the study inclusion criteria, namely, a history of HSCT following very early or early relapse of B-ALL, with blinatumomab administered for remission induction. The median age was 5 years (range 5 - 12 years). All were boys. Of them, one child had a second relapse whereas the rest presented with early combined relapse (one), late isolated medullar relapse with positive MRD at end of induction (one), early isolated medullary relapse (one), and very early combined relapse (one). All were treated on conventional protocols at initial diagnosis (BFM 95/modified BFM 2009-3, ICICLE-2). Details of individual patients, transplant-related variables, and outcome are presented in Table 1. Blinatumomab was administered exclusively as a continuous inpatient infusion for all five children, with no ambulatory pump or home-based delivery. This approach was necessitated by limited feasibility of safe home monitoring, particularly due to caregiver educational constraints and lack of community support for close clinical supervision and timely management of potential toxicities.

Click to view | Table 1. Baseline Characteristics and Disease Profile of Pediatric Patients With Relapsed B-Cell Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia Treated With Blinatumomab Prior to HSCT |

All patients completed 1 - 2 cycles of 28-day infusion of blinatumomab without interruption. No patient developed neurologic toxicity or clinically significant cytokine release syndrome (CRS) requiring directed therapy. At our center, we offered blinatumomab in two patients who had severe infections (mucormycosis of gluteal soft tissue and methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus-associated cellulitis of leg) and prior liver dysfunction as conventional chemotherapy would have been difficult. At the end of the cycle, MRD done was < 0.01% in all five patients, allowing timely progression to HSCT. The median interval from completion of blinatumomab to conditioning initiation was 4 weeks (range 21 - 45 days).

Operational handling and monitoring procedures

Blinatumomab storage, preparation, and administration followed institutional cytotoxic drug handling policies. The drug was stored under cold-chain conditions at 2 - 8 °C and reconstituted under aseptic techniques in a certified biological safety cabinet. Prepared infusion bags were protected from light, and stability guidelines were adhered to. All five children received continuous inpatient intravenous infusion for each 28-day cycle, overseen by trained pediatric oncology nursing staff, with no ambulatory or pump-based home delivery. Nurses were trained in central venous access device care with instructions not to flush the line with blinatumomab and trained in careful monitoring for fever and features of cytokine release and neurological effects. Nursing documentation was standardized, and escalation pathways for suspected CRS or neurotoxicity were predefined, although such events were not encountered in this cohort.

HSCT

The donor sources for HSCT were MSD (n = 1), and haploidentical family donors (n = 4: father, n = 3; brother, n = 1) in the rest. Myeloablative conditioning was used in all patients. Granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (GCSF) was used for mobilization in all donors. Peripheral blood stem cell apheresis was done on day 5 in one setting for all. Plerixafor was used as an additional mobilizing agent in one donor, who was donating stem cells for his haploidentical brother, due to concerns related to low donor weight. The CD34+ stem cell dose used was 5.5 × 106/kg of the recipient for the child undergoing matched donor HSCT and a median of 9.7 × 106/kg (range 5.5 - 24 × 106/kg) for haploidentical transplant recipients. Neutrophil engraftment (ANC > 500/µL) occurred at a median of day +12 (range 11 - 12) and platelet engraftment (> 20,000/µL unsupported) on day +9 (range 7 - 15). Discharge after HSCT was done at a median of 42 days (range 31 - 64 days).

Infectious complications

All patients were on antiviral (acyclovir) and antifungal prophylaxis (posaconazole/voriconazole) prior to conditioning. None received antibacterial prophylaxis. IgG replacement with intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) at 400 mg/kg was given to all with trough level < 400 mg/dL.

Febrile neutropenia was reported in all patients in the cytopenic period, which was managed as per standard protocols. One child had septic shock, which was managed with inotrope support and granulocyte infusions. None of the patients had a positive blood culture. One child had documented urinary tract infection with E. coli, and another had Clostridium difficile enterocolitis, which were managed with sensitive antibiotics.

We noticed CMV reactivation in all patients who underwent haploidentical HSCT (4/5). Of these, three children were treated with intravenous ganciclovir and one required foscarnet due to concurrent cytopenias. As two children had associated GVHD, response time was variable. Following induction therapy, all patients received valganciclovir until clearance was documented by two consecutive negative viral PCR assays, after which antiviral prophylaxis was continued on acyclovir. EBV reactivation was noted in one patient around +60 days post-transplant; no specific treatment was offered in view of tapering of immunosuppression and lack of any clinical features.

Non-infectious complications

Engraftment syndrome as evidenced by hectic fever, skin rash, and weight gain was observed in all patients who underwent haploidentical HSCT (4/5); all responded to a short course of steroids. None had severe engraftment syndrome; there was no requirement for supplemental oxygen or evidence of multiorgan dysfunction.

Grade III mucositis was reported in two children, which improved upon recovery of counts. Acute GVHD was reported in two out of five patients. Both had received haploidentical transplantation. One child had skin and gut GVHD (grade III/stage III), whereas the other child has gut limited GVHD (grade III/stage III). Both were steroid-refractory and ruxolitinib was added, following which there was improvement. We did not observe sinusoidal obstruction syndrome or thrombotic microangiopathy and no transplant-related deaths occurred during the follow-up period.

As described earlier, chimerism and remission status (MRD and CSF) was assessed initially between day +28 and +35 based on clinical condition of the patient. The child who underwent matched sibling donor HSCT, following thiotepa-fludarabine-busulfan, had a peripheral blood donor chimerism of 87.6% on day +21. This improved to 100% by day 60 and has remained so till date (1,015 days since transplantation). Full donor chimerism was noted for all haploidentical transplant recipients from day +28 onwards.

The median follow-up as of September 1, 2025 was 173 days (52 - 1,015 days), and all patients remained in MRD-negative remission, with clearance of CMV and 100% donor chimerism at last follow-up. Out of the two children who started on immunosuppression, one continued to be on tapering doses of ruxolitinib without GVHD. Kaplan-Meier estimates for OS and FFS remained at 100% at last follow-up.

| Discussion | ▴Top |

Access to immunotherapy is considered a breakthrough for children with relapsed ALL, as it offers targeted and highly effective anti-leukemic approach without myelosuppression and associated toxicities of conventional chemotherapy. It can offer deeper remissions, thus achieving MRD-negative disease prior to HSCT even in chemo-resistant disease, and reduce need for supportive care including infrastructure, antimicrobials, transfusions, and potential for even outpatient administration. In LMICs, the cost of procuring the drug is exorbitant, thus limiting its use immensely. The efficacy has been demonstrated not only in high-risk relapses, but even in upfront settings in both infants and children [10-13].

Blinatumomab, a bispecific CD19 and CD3 T-cell engager that redirects cytotoxic T cells to CD19-expressing B-lineage blasts, leading to targeted cytotoxicity is more efficacious and less toxic than conventional chemotherapy. However, as it causes rapid and prolonged B-cell depletion, causing even CD19-negative plasma cell depletion, due to clearance of precursors, low immunoglobulin levels have been reported which recover over time. Infections of any grade are reported much lesser in blinatumomab arm compared to conventional chemotherapy. Immunoglobulin replacement is recommended as standard practice in these patients to reduce the risk of infections.

In our series of five patients, all with high-risk relapse of B-ALL, universal MRD negativity was achieved after a single 28-day cycle in all five patients thus enabling timely transplantation, robust engraftment, and full donor chimerism. Although febrile neutropenia was reported in all, none had a positive culture, and all recovered with standard of care. So also, the other infections noted were also amenable to cure without any complications.

In reported literature evaluating the influence of HSCT on blinatumomab-treated patients, the rates of acute and chronic GVHD are similar with no reproducible increase in severe acute GVHD. Infections also have been reported to be similar; however, the data are mainly from high-income countries with access to prophylaxis against CMV in high-risk donor-recipient combinations which is out of reach for LMICs. Engraftment kinetics and graft failure are noted to be similar with no causal link to blinatumomab from the observational mainly retrospective data. Non-relapse mortality and early transplant-related mortality are predictably low in patients who received prior blinatumomab [14, 15]. Relapse remains the dominant failure post-HSCT where other modalities of immunotherapy or chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapies have been explored.

The incidence of engraftment syndrome was high; 100% of patients who underwent haploidentical HSCT required steroid support for a short period. Transplant-related CMV reactivations were also reported to be high. Due to resource constraints, CMV prophylaxis was not offered to any. These findings emphasize that while blinatumomab may reduce myelosuppression in the pre-transplant remission and offer quicker, deeper, and gentler remissions, the transplant period remains high risk for immune and infectious complications that require robust supportive care pathways.

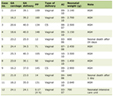

Table 2 summarizes the trial data and real-world experience of outcomes of HSCT following blinatumomab exposure in children with relapsed/refractory B-ALL across both high-income and LMIC settings. In either settings, and across income levels, there is no major attributable risk for infectious or non-infectious complications post-HSCT [6, 15-20]. However, outside trials, the numbers are small, with heterogeneity in inclusion criteria, supportive care, and short follow-up to preclude any definitive conclusion.

Click to view | Table 2. Summary of Trial and Real-World Outcomes of HSCT Following Blinatumomab in Pediatric Relapsed B-ALL Across Different Gross National Income Groups |

Access and cost considerations in LMICs

The limiting factor for wider use of blinatumomab in LMICs is cost. Drug acquisition costs are substantial, as the patient access program operated by Amgen Blinatumomab Humanitarian Access Program in collaboration with St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital and Direct Relief is operational only in few hospitals in the country. As the cost of treatment in these hospitals (other than the drug which is free) is beyond the reach for poor families, referral for the drug is not practical. In our series, two patients had access to the drug through another center which has access to patient assistance program. The three patients who received blinatumomab procured it through external philanthropy or employer insurance of the parent. Practical guidance regarding pharmacy handling, monitoring standards, and complication preparedness may facilitate wider and safer implementation of blinatumomab-supported HSCT in resource-constrained settings.

Strengths and limitations

We report peri-transplantation outcome for a select cohort of high-risk pediatric B-ALL with co-morbidities such as life-threatening infections who underwent HSCT, without any additional toxicity after having attained MRD-negative remission with the use of 1 - 2 cycles of blinatumomab. The limitations include small sample size, single-center retrospective design, potential selection bias as moribund patients would not have received blinatumomab, and the relatively short follow-up for late relapses and chronic GVHD outcomes. So also, the comparator group treated with conventional salvage chemotherapy has not been reported in this paper. Additionally, MRD was assessed using multiparameter flow cytometry rather than next-generation sequencing (NGS), which offers greater sensitivity; however, NGS-based MRD platforms are not widely accessible in India and remain cost-prohibitive in most LMIC settings. Larger, prospective, multicenter registries can help validate our findings, optimize bridging strategies, post-transplantation immune and infectious surveillance, and perform robust cost-effectiveness analyses. Such data could also help increase the access to these drugs to public sector hospitals that bear the brunt of high patient load and multidrug-resistant infections, which deter treatment with conventional chemotherapy.

Conclusions

HSCT was tolerated well without increased risk of serious infections post-HSCT. Universal MRD negativity, reliable engraftment, and excellent short-term survival were observed; however, engraftment syndrome, viral reactivations, and steroid-refractory GVHD were noted. The data support the need for enhanced infection surveillance and immune monitoring post-HSCT in this cohort of patients.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge that the primary treatment including blinatumomab for two of these children was provided at Homi Bhabha Cancer Hospital, Varanasi, Uttar Pradesh. They underwent HSCT at our center after remission was achieved. We acknowledge the support received from various central and state government schemes for treatment of these patients.

Financial Disclosure

No external funding was obtained for this retrospective analysis.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest related to this manuscript.

Informed Consent

Since outcome was reported from chart review, waiver of informed consent was obtained.

Author Contributions

AT, AS, NR, HG, and SB were involved in patient care and clinical management. ASr contributed to data collection and compilation. All authors participated in manuscript preparation, critical revision, and approved the final version for submission.

Data Availability

The data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. Any inquiries regarding data availability should be directed to the corresponding author.

| References | ▴Top |

- Sidhu J, Gogoi MP, Krishnan S, Saha V. Relapsed acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Indian J Pediatr. 2024;91(2):158-167.

doi pubmed pmc - Korrapolu RSA, Boddu D, John R, Antonisamy N, Geevar T, Arunachalam AK, Joseph LL, et al. What happens to children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia in low- and middle-income countries after relapse? A single-center experience from India. Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2023;40(5):475-484.

doi pubmed - Roy Moulik N, Keerthivasagam S, Velagala SV, Gollamudi VRM, Agiwale J, Dhamne C, Chichra A, et al. Treating relapsed B cell-precursor ALL in children with a setting-adapted mitoxantrone-based intensive chemotherapy protocol (TMH rALL-18 PROTOCOL) - experience from Tata Memorial Hospital, India. Ann Hematol. 2023;102(10):2835-2844.

doi pubmed - Thakkar D, Upasana K, Udayakumar DS, Rastogi N, Chadha R, Arora S, Jha B, et al. Treatment of pediatric acute lymphoblastic leukemia in India as per modified BFM 95 protocol with minimal residual disease monitoring. Hematology. 2025;30(1):2439733.

doi pubmed - Pawinska-Wasikowska K, Wieczorek A, Balwierz W, Bukowska-Strakova K, Surman M, Skoczen S. Blinatumomab as a bridge therapy for hematopoietic stem cell transplantation in pediatric refractory/relapsed acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Cancers (Basel). 2022;14(2):458.

doi pubmed pmc - Chadha V, Nirmal G, Chatterjee G, Paul Subhasish, Singh G, Gupta N, Kharya G. et al. Blinatumomab-based salvage in relapsed/refractory B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia: "real world" experience from a single-centre in India. Pediatr Hematol Oncol J. 2025;10(2):100447.

doi - Luznik L, Fuchs EJ. High-dose, post-transplantation cyclophosphamide to promote graft-host tolerance after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Immunol Res. 2010;47(1-3):65-77.

doi pubmed pmc - Bader P, Kreyenberg H, von Stackelberg A, Eckert C, Salzmann-Manrique E, Meisel R, Poetschger U, et al. Monitoring of minimal residual disease after allogeneic stem-cell transplantation in relapsed childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia allows for the identification of impending relapse: results of the ALL-BFM-SCT 2003 trial. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(11):1275-1284.

doi pubmed - Sureda A, Corbacioglu S, Greco R, Kroger N, Carreras E, eds. The EBMT handbook: hematopoietic cell transplantation and cellular therapies. 8th ed. Cham (CH): Springer; 2024.

doi pubmed - Locatelli F, Zugmaier G, Rizzari C, Morris JD, Gruhn B, Klingebiel T, Parasole R, et al. Effect of blinatumomab vs chemotherapy on event-free survival among children with high-risk first-relapse B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2021;325(9):843-854.

doi pubmed pmc - Brown PA, Ji L, Xu X, Devidas M, Hogan LE, Borowitz MJ, Raetz EA, et al. Effect of postreinduction therapy consolidation with blinatumomab vs chemotherapy on disease-free survival in children, adolescents, and young adults with first relapse of B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2021;325(9):833-842.

doi pubmed pmc - van der Sluis IM, de Lorenzo P, Kotecha RS, Attarbaschi A, Escherich G, Nysom K, Stary J, et al. Blinatumomab added to chemotherapy in infant lymphoblastic leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2023;388(17):1572-1581.

doi pubmed - Gupta S, Rau RE, Kairalla JA, Rabin KR, Wang C, Angiolillo AL, Alexander S, et al. Blinatumomab in standard-risk B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia in children. N Engl J Med. 2025;392(9):875-891.

doi pubmed pmc - Maschmeyer G, De Greef J, Mellinghoff SC, Nosari A, Thiebaut-Bertrand A, Bergeron A, Franquet T, et al. Infections associated with immunotherapeutic and molecular targeted agents in hematology and oncology. A position paper by the European Conference on Infections in Leukemia (ECIL). Leukemia. 2019;33(4):844-862.

doi pubmed pmc - Algeri M, Massa M, Pagliara D, Bertaina V, Galaverna F, Pili I, Li Pira G, et al. Outcomes of children and young adults with B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia given blinatumomab as last consolidation treatment before allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Haematologica. 2025;110(3):596-607.

doi pubmed pmc - von Stackelberg A, Locatelli F, Zugmaier G, Handgretinger R, Trippett TM, Rizzari C, Bader P, et al. Phase I/Phase II study of blinatumomab in pediatric patients with relapsed/refractory acute lymphoblastic leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(36):4381-4389.

doi pubmed - Locatelli F, Zugmaier G, Mergen N, Bader P, Jeha S, Schlegel PG, Bourquin JP, et al. Blinatumomab in pediatric relapsed/refractory B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia: RIALTO expanded access study final analysis. Blood Adv. 2022;6(3):1004-1014.

doi pubmed pmc - Llaurador G, Shaver K, Wu M, Wang T, Gillispie A, Doherty E, Craddock J, et al. Blinatumomab therapy is associated with favorable outcomes after allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation in pediatric patients with B cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Transplant Cell Ther. 2024;30(2):217-227.

doi pubmed - Lu J, Bao X, Zhou J, Li X, He Z, Ji Y, Xue S, et al. Safety and efficacy of blinatumomab as bridge-to-transplant for B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia in first complete remission with no detectable minimal residual disease. Blood Cancer J. 2024;14(1):143.

doi pubmed pmc - Sayyed A, Chen C, Gerbitz A, Kim DDH, Kumar R, Lam W, Law AD, et al. Pretransplant blinatumomab improves outcomes in B cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia patients who undergo allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation. Transplant Cell Ther. 2024;30(5):520.e521-520.e512.

doi pubmed

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial 4.0 International License, which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Journal of Hematology is published by Elmer Press Inc.