| Journal of Hematology, ISSN 1927-1212 print, 1927-1220 online, Open Access |

| Article copyright, the authors; Journal compilation copyright, J Hematol and Elmer Press Inc |

| Journal website https://jh.elmerpub.com |

Case Report

Volume 000, Number 000, October 2025, pages 000-000

Bilateral Avascular Necrosis of the Hips in a Patient With Sickle Cell Trait and Chronic Alcohol Use

Sarah Al-Zahera, c, Janan Niknama, Sivarama K. Kotikalapudib

aDepartment of Clinical Sciences, William Carey University College of Osteopathic Medicine, Hattiesburg, MS 39401, USA

bDepartment of Internal Medicine, Southern Star Medical Group, Hattiesburg, MS 39402, USA

cCorresponding Author: Sarah Al-Zaher, Department of Clinical Sciences, William Carey University College of Osteopathic Medicine, Hattiesburg, MS 39401, USA

Manuscript submitted May 21, 2025, accepted August 14, 2025, published online October 10, 2025

Short title: Bilateral Hip AVN in SCT and Alcohol Use

doi: https://doi.org/10.14740/jh2084

| Abstract | ▴Top |

Sickle cell trait (SCT) is generally considered a benign carrier state, unlike sickle cell disease (SCD), which is frequently associated with complications such as avascular necrosis (AVN). While AVN affects approximately 30% of patients with SCD, it is rarely reported in individuals with SCT and is not well understood. A 29-year-old African American male with SCT presented with progressively worsening hip pain. He reported chronic heavy alcohol use but denied steroid use, trauma or previous sickle cell crises. Physical exam demonstrated severely limited hip range of motion and antalgic gait. Laboratory studies were unremarkable aside from elevated C-reactive protein. Radiographs revealed bilateral femoral head AVN greater than stage II, with partial collapse on the left. He was managed conservatively with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), physical therapy, and counseling on alcohol reduction, and was referred to orthopedics for long-term management. Although rare, AVN can occur in individuals with SCT, particularly when compounded by modifiable risk factors such as chronic alcohol use, which can impair bone remodeling, promote fat embolism, and exacerbate microvascular compromise from intermittent sickling. It highlights the importance of early recognition and intervention in patients with unexplained joint pain, and that clinicians should maintain a high index of suspicion for AVN in SCT patients, especially in the presence of other comorbidities and risk factors.

Keywords: Sickle cell trait; Avascular necrosis; Femoral head; Osteonecrosis; Chronic alcohol use; Hip pain

| Introduction | ▴Top |

Sickle cell disease (SCD) is the most common genetic disease in the United States, affecting 1 in 500 African American [1]. It is characterized by chronic hemolytic anemia and vaso-occlusive episodes that can lead to widespread organ and skeletal complications, including avascular necrosis (AVN) [2]. AVN is a frequent and severe complication in patients with SCD, affecting approximately 30% of individuals, often bilaterally, involving the femoral head [2]. The underlying pathophysiology is attributed to repeated microvascular occlusion by sickled red blood cells, resulting in localized ischemia, infarction of bone and marrow tissue, and eventual structural collapse [2, 3].

Sickle cell trait (SCT), which arises from the heterozygous inheritance of one normal beta-globin gene and one sickle gene (HbAS), is generally considered a benign condition [3]. Patients with SCT are generally asymptomatic and usually do not experience any vaso-occlusive phenomena or severe complications associated with SCD [4]. AVN is much less common in individuals with SCT, who typically do not experience the severe vaso-occlusive episodes characteristic of SCD [5]. The pathophysiologic mechanism of AVN in SCT remains poorly understood but may involve intermittent sickling under hypoxic or hyperosmolar conditions, leading to transient vascular obstruction [6]. Although such complications are infrequent, their presence in SCT patients demands the need for greater awareness and further research [6]. AVN has been strongly associated with other well-established risk factors, including long-term corticosteroid use, systemic lupus erythematosus, and excessive alcohol consumption, the latter of which may impair bone remodeling processes and contribute to microvascular injury [6].

Despite these potential associations, reports of AVN occurring in SCT patients are scarce. Several case reports and small series - such as those by Eholie et al [7], Brown et al [8], and Banait et al [9] - have documented AVN in SCT patients, often in the setting of other risk factors including alcohol use, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), hypertriglyceridemia, or corticosteroid therapy, suggesting SCT may act as a cofactor rather than a sole cause.

Here, we present the case of a 29-year-old African American male with SCT with bilateral hip pain, who was diagnosed with bilateral AVN, contributing to the growing body of evidence that SCT may predispose individuals to serious skeletal complications under certain conditions. This case highlights the potential for severe musculoskeletal complications even in individuals with SCT and the importance of early diagnosis and multidisciplinary management to prevent long-term disability.

| Case Report | ▴Top |

Investigations

A 29-year-old African American male presented to the clinic with progressively worsening bilateral hip pain over the past year. Initially, the discomfort was mild and occurred only after prolonged standing or climbing stairs. However, over the last 6 months, the pain had intensified to the point of limiting daily activities, such as walking more than a few blocks or sitting cross-legged. He rated his pain as 6/10 at baseline and up to 9/10 with movement. The patient denied any history of injury or trauma. He had been taking diclofenac 75 mg by mouth twice a day, which provided partial relief. There were no associated constitutional symptoms such as fever, weight loss, or malaise. Although unable to quantify the exact amount, the patient reported consuming approximately five to six alcoholic beverages daily for the past 6 years. He denied tobacco, recreational drugs and steroid use. His family history was notable for SCD in his sister and niece. He denied having experienced any acute episodes of sickle cell symptoms and was unaware of his carrier status until recently identified as having SCT.

Physical examination revealed severely decreased range of motion in internal and external rotation of the bilateral hips, with approximately 25° of internal rotation and less than 5° of external rotation. The left hip had slightly more decreased range of motion with flexion to approximately 90-95°. An antalgic gait was observed. Neurological and vascular exams of the lower extremities were normal.

Diagnosis

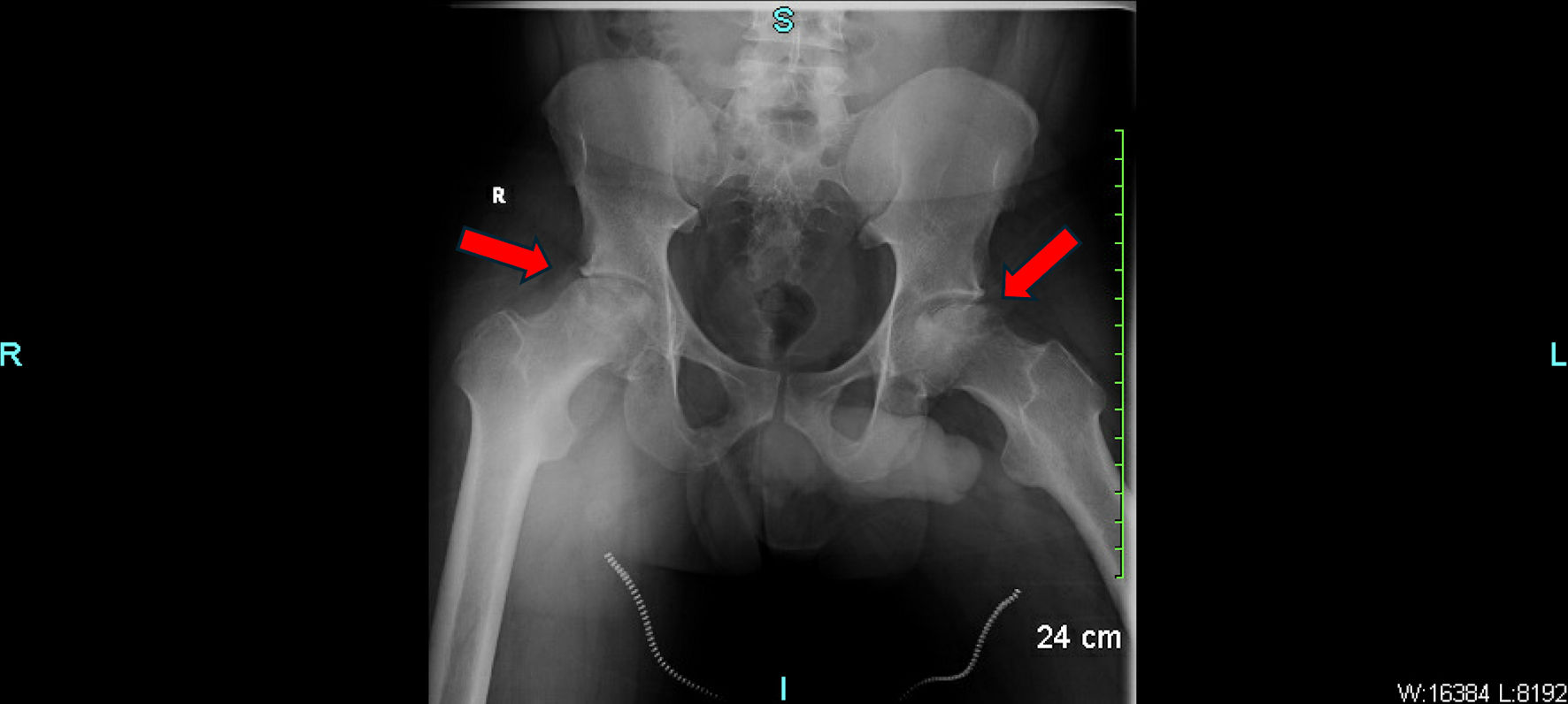

Laboratory results were unremarkable except for an elevated C-reactive protein (8.90 mg/L, reference < 3.01 mg/L). Complete blood count, renal function, liver enzymes, and urinalysis were within normal limits. Hemoglobin was 13.2 g/dL. High-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) confirmed the diagnosis of SCT (AS pattern), with HbA comprising approximately 60% and HbS approximately 40%, while HbA2 and HbF were within normal limits, consistent with the heterozygous state. Pelvic X-rays demonstrated advanced AVN of both femoral heads, greater than stage II. The left femoral head showed partial collapse, irregularity, and joint space narrowing. No signs of fracture, osteophyte formation, or joint effusion were noted (Fig. 1).

Click for large image | Figure 1. Pelvic X-ray showing advanced avascular necrosis of the bilateral femoral heads with partial cortical collapse. The red arrows indicate areas of sclerotic changes, subchondral lucency, and femoral head flattening consistent with AVN. AVN: avascular necrosis. |

Treatment

The patient was advised to continue diclofenac for pain management and was referred for therapeutic glucocorticoid injections if needed. Nonoperative interventions, including physical therapy, were recommended. He was counseled to reduce his alcohol intake, given its potential role in his progressive hip pain. He was also referred to an orthopedic consult for further evaluation and long-term management, including potential surgical options such as total hip arthroplasty (THA) if symptoms progressed.

Follow-up and outcomes

At follow-up, the patient reported modest symptomatic relief with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and physical therapy. He is currently unwilling to proceed with surgery. Follow-up every 3 months with repeat radiographs was advised to monitor for worsening femoral head collapse.

| Discussion | ▴Top |

AVN, or osteonecrosis, is a progressive condition characterized by ischemic injury to bone tissue, ultimately leading to structural collapse and joint dysfunction [6]. It most commonly affects the femoral head due to its reliance on terminal blood supply and limited collateral circulation [6]. In patients with SCD, AVN is a frequent and well-documented complication resulting from repeated vaso-occlusive crises that obstruct microvascular perfusion and impair oxygen delivery to the bone [6].

This case report presents a patient who initially sought care for bilateral hip pain and was subsequently diagnosed with AVN, leading to the incidental discovery of SCT. Compared to its high prevalence in patients with SCD, AVN is an extremely rare complication in individuals with SCT [6]. There is no clear evidence that individuals with SCT have vaso-occlusive pain events similar to those seen with SCD [8]. Unless SCT is co-inherited with another hemoglobinopathy, the incidence of vaso-occlusive phenomena is low and not well understood [8]. It is important to consider other potential causes that have long been linked to AVN, such as alcohol abuse, glucocorticoid therapy, and autoimmune conditions, as the direct association between SCT and AVN still remains unclear [10]. While alcohol alone may be sufficient to cause AVN, the co-existence of SCT may have compounded the risk through microvascular compromise, potentially acting as an adjuvant factor rather than a primary cause in this patient’s case.

While only a small percentage of patients with alcohol use disorder develop osteonecrosis, excessive alcohol intake has been identified as a contributing factor in up to 31% of AVN cases [11]. Chronic heavy alcohol use can lead to fatty liver changes, hyperlipidemia and fat emboli, which can obstruct the microcirculation in the bone, leading to ischemia and subsequent necrosis [12]. Additionally, alcohol may impair bone remodeling and repair processes, further contributing to the development of AVN [12]. In this patient, the absence of other major risk factors supports alcohol use as a likely etiologic factor. The combination of SCT and alcohol use can synergistically increase the risk of AVN, as alcohol-induced fat emboli and the sickling of red blood cells can together compromise blood supply to the femoral head, exacerbating the risk. This case highlights the importance of addressing modifiable risk factors, such as alcohol use, in the management and prevention of AVN, especially in patients with SCT.

Although radiographs were sufficient for diagnosis in this case, the absence of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) represents a diagnostic limitation. MRI remains the gold standard for early detection of AVN, particularly in asymptomatic or for early detection of AVN [13]. Incorporating MRI with this patient might have provided additional insights into the extent of femoral head involvement and could have informed more nuanced management decisions, particularly in evaluating surgical candidacy. However, in this case, advanced AVN with structural collapse was already evident on plain radiography, allowing for confident diagnosis and timely referral to orthopedic services. The decision to forego MRI was based on financial considerations, as the patient expressed inability to afford advanced imaging.

Although literature on AVN in SCT remains sparse, several published reports illustrate that it can occur, particularly in the presence of additional risk factors. Tsaras et al reviewed SCT-associated complications and emphasized that, although typically asymptomatic, SCT can result in clinically significant manifestations - such as AVN - when exposed to environmental or physiological stressors [6]. For example, Eholie et al [7] documented three cases of AVN in SCT patients, each of whom had additional contributing conditions such as HIV infection, hypertriglyceridemia, or alcohol abuse - reinforcing the idea that SCT may function as an adjuvant risk factor rather than a sole etiology. Brown et al [8] described a case series of three patients with SCT who developed multifocal AVN involving the hips, shoulders, and knees that all required surgical intervention. Although each patient had at least one additional risk factor, such as steroid use or alcohol, the extent and severity of AVN raised concern for SCT as a contributing cofactor [9]. These findings align with the present case, in which chronic alcohol use likely played a primary pathogenic role, while SCT may have compounded the risk by contributing to intermittent microvascular compromise. As such, this case highlights the importance of evaluating SCT patients holistically, with close attention to modifiable and additive risk factors when they present with unexplained joint pain.

A similar case was presented by Banait et al [9] describing a 25-year-old female with SCT who developed bilateral humeral head AVN. In this case, the patient presented with shoulder pain that had persisted for 3 months, and imaging confirmed AVN in both shoulder joints [9]. This case emphasized that, while SCT is generally considered benign, it may still lead to severe complications such as AVN under certain conditions [9]. The patient had no known comorbidities, and the authors concluded that AVN should be included in the differential diagnosis when patients with SCT present with unexplained joint pain, reinforcing the need for early imaging and diagnosis to prevent delayed management and functional decline.

Management of AVN depends on the severity and stage of disease. Initially, management should prioritize nonoperative interventions, including continued use of analgesics and anti-inflammatory agents such as diclofenac, physical therapy to maintain joint function and activity modification to reduce stress on the hips [14]. In early-stage AVN, when femoral head morphology is preserved, core decompression - with or without bone grafting - may be considered to relieve intraosseous pressure and improve vascularity. Alternative joint-preserving approaches include vascularized fibular grafting, tantalum implants, and osteotomies, which aim to support bone structure, reduce mechanical load, and delay joint collapse [15]. However, in advanced cases with subchondral collapse, as in this patient, core decompression is generally not appropriate, and surgical options such as THA are more suitable [14]. THA has been shown to significantly improve pain and function in SCD patients, despite the higher risk of complications in sickle cell patients, such as infection, and pain crises [16]. Similar benefits may be expected in SCT patients with AVN, although data specific to SCT are limited [17]. Nonetheless, proper perioperative planning and multidisciplinary care remain essential to optimizing outcomes in this population [17]. Given the patient’s current reluctance to undergo surgery, it is reasonable to continue with conservative management and regular follow-up with repeat radiographs; however, if conservative measures fail, revisiting the option of THA may be necessary.

This case contributes to the limited literature on AVN in SCT and reinforces the need for a high index of suspicion when evaluating joint pain, especially in the presence of modifiable risk factors. Early diagnosis and longitudinal follow-up can aid in preserving joint function and preventing disability. Further research is warranted to better characterize the pathophysiological link between SCT and AVN, and to guide evidence-based management strategies in this subset of patients. As with all case reports, conclusions are inherently limited by the single-patient design and should be interpreted with caution. Larger studies are needed to clarify the potential association between SCT and AVN.

Patient perspective

The patient expressed concern over his mobility and quality of life. Despite being offered surgical options, the patient voiced concerns about recovery time, complications, and the potential financial burden, which contributed to his decision to pursue nonoperative management initially. He was appreciative of the multidisciplinary approach, including physical therapy and counseling on alcohol use, and expressed a commitment to making lifestyle changes. At follow-up, he acknowledged feeling more empowered by understanding his condition and was open to reconsidering surgical intervention in the future if symptoms worsened.

Learning points

This case shows that AVN can occur in patients with SCT, even in the absence of SCD or typical vaso-occlusive events. It challenges the longstanding perception of SCT as being entirely benign and emphasizes the importance of maintaining a high index of suspicion for AVN in patients presenting with unexplained joint pain, and may be potentiated by co-existing risk factors. In this case, chronic alcohol consumption likely played a role. Alcohol use has been implicated in up to 31% of AVN cases and contributes through mechanisms including fat embolism, altered lipid metabolism, and impaired bone healing, and may exacerbate microvascular compromise in patients with SCT. Early recognition of AVN through appropriate imaging is essential for preserving joint integrity and function, especially in young adults with progressive symptoms. This case also highlights the value of patient-centered care, where shared decision-making and counseling around lifestyle modification can support long-term outcomes and readiness for potential surgical intervention.

Acknowledgments

None to declare.

Financial Disclosure

The authors declare that there was no financial support or funding for this work.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Informed Consent

The patient has provided written consent for the use of his medical information in the writing of the present report.

Author Contributions

Sarah Al-Zaher: primary author, literature review, clinical case analysis, manuscript drafting. Janan Niknam: manuscript editing, literature review, figure formatting, and reference support. Sivarama K. Kotikalapudi, MD: clinical case supervision, final manuscript review.

Data Availability

The authors declare that data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article.

| References | ▴Top |

- Sedrak A, Kondamudi NP. Sickle cell disease (Archived). In: StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL) ineligible companies. 2025.

pubmed - Alshurafa A, Soliman AT, De Sanctis V, Ismail O, Abu-Tineh M, Hemadneh MKE, Rashid FR, et al. Clinical and epidemiological features and therapeutic options of avascular necrosis in patients with sickle cell disease (SCD): a cross-sectional study. Acta Biomed. 2023;94(5):e2023198.

doi pubmed - Williams TN, Thein SL. Sickle cell anemia and its phenotypes. Annu Rev Genomics Hum Genet. 2018;19:113-147.

doi pubmed - Inusa BPD, Hsu LL, Kohli N, Patel A, Ominu-Evbota K, Anie KA, Atoyebi W. Sickle cell disease-genetics, pathophysiology, clinical presentation and treatment. Int J Neonatal Screen. 2019;5(2):20.

doi pubmed - Weeks LD, Wilson AM, Naik RP, Efebera Y, Murad MH, Mahajan A, McGann PT, et al. Sickle cell trait does not cause "sickle cell crisis" leading to exertion-related death: a systematic review. Blood. 2025;145(13):1345-1352.

doi pubmed - Tsaras G, Owusu-Ansah A, Boateng FO, Amoateng-Adjepong Y. Complications associated with sickle cell trait: a brief narrative review. Am J Med. 2009;122(6):507-512.

doi pubmed - Eholie SP, Ello F, Ouattara B, et al. Avascular osteonecrosis of the femoral head in three patients with sickle cell trait. Rev Rhum Engl Ed. 1997;64(2):123-126.

- Brown TS, Lakra R, Master S, Ramadas P. Sickle cell trait: is it always benign? J Hematol. 2023;12(3):123-127.

doi pubmed - Banait S, Banait T, Shukla S, Mane S, Jain J. Bilateral humeral head avascular necrosis: a rare presentation in sickle cell trait. Cureus. 2023;15(8):e44006.

doi pubmed - Bickley MK, Li J, Mackay ND, Chapman AW. Avascular necrosis of the foot and ankle: aetiology, investigation and management. Orthop Trauma. 2023;37(1):40-48.

- Lespasio MJ, Sodhi N, Mont MA. Osteonecrosis of the hip: a primer. Perm J. 2019;23:18-100.

doi pubmed - Narayanan A, Khanchandani P, Borkar RM, Ambati CR, Roy A, Han X, Bhoskar RN, et al. Avascular necrosis of femoral head: a metabolomic, biophysical, biochemical, electron microscopic and histopathological characterization. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):10721.

doi pubmed - Manenti G, Altobelli S, Pugliese L, Tarantino U. The role of imaging in diagnosis and management of femoral head avascular necrosis. Clin Cases Miner Bone Metab. 2015;12(Suppl 1):31-38.

doi pubmed - Lohiya A, Jr., Dhaniwala N, Dudhekar U, Goyal S, Patel SK. A comprehensive review of treatment strategies for early avascular necrosis. Cureus. 2023;15(12):e50510.

doi pubmed - Jokubynas VV, Patel AA, Singh K, et al. Surgical management of avascular necrosis: joint-preserving versus arthroplasty options. J Med Sci. 2025;7(1):15-27.

- Kenanidis E, Kapriniotis K, Anagnostis P, Potoupnis M, Christofilopoulos P, Tsiridis E. Total hip arthroplasty in sickle cell disease: a systematic review. EFORT Open Rev. 2020;5(3):180-188.

doi pubmed - Waters TL, Wilder JH, Ross BJ, Salas Z, Sherman WF. Effect of sickle cell trait on total hip arthroplasty in a matched cohort. J Arthroplasty. 2022;37(5):892-896.e895.

doi pubmed

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial 4.0 International License, which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Journal of Hematology is published by Elmer Press Inc.